In one of our previous articles, we took you on a tour of the university’s optoelectronics lab. This time around we’ve got something more public, but no less exciting in mind: The Optics Museum.

Bandwidth warning: lots of photos below!

The museum of optics is located in the former building of the Vavilov State Optical Institute on Vasilevskiy Island. In 2007, when the historic neighbourhood behind the old Stock Exchange was being renovated, the institute’s staff had to decide the building’s fate. That’s when, inspired by the growing edutainment movement, Sergei Stafeev of the physics and engineering department proposed the idea of the museum.

The museum was initially designed to promote the study of optics, and showcase the potential of the field to those who’re yet to choose a career. For the first few years, it was closed to the general public and could only be visited by guided school groups. 2015 saw the opening of the Magic of Light permanent exhibition — an interactive pop-sci journey into optics spread over 10 thousand square feet of space.

With it, the museum started operating regular hours and welcoming solo visitors.

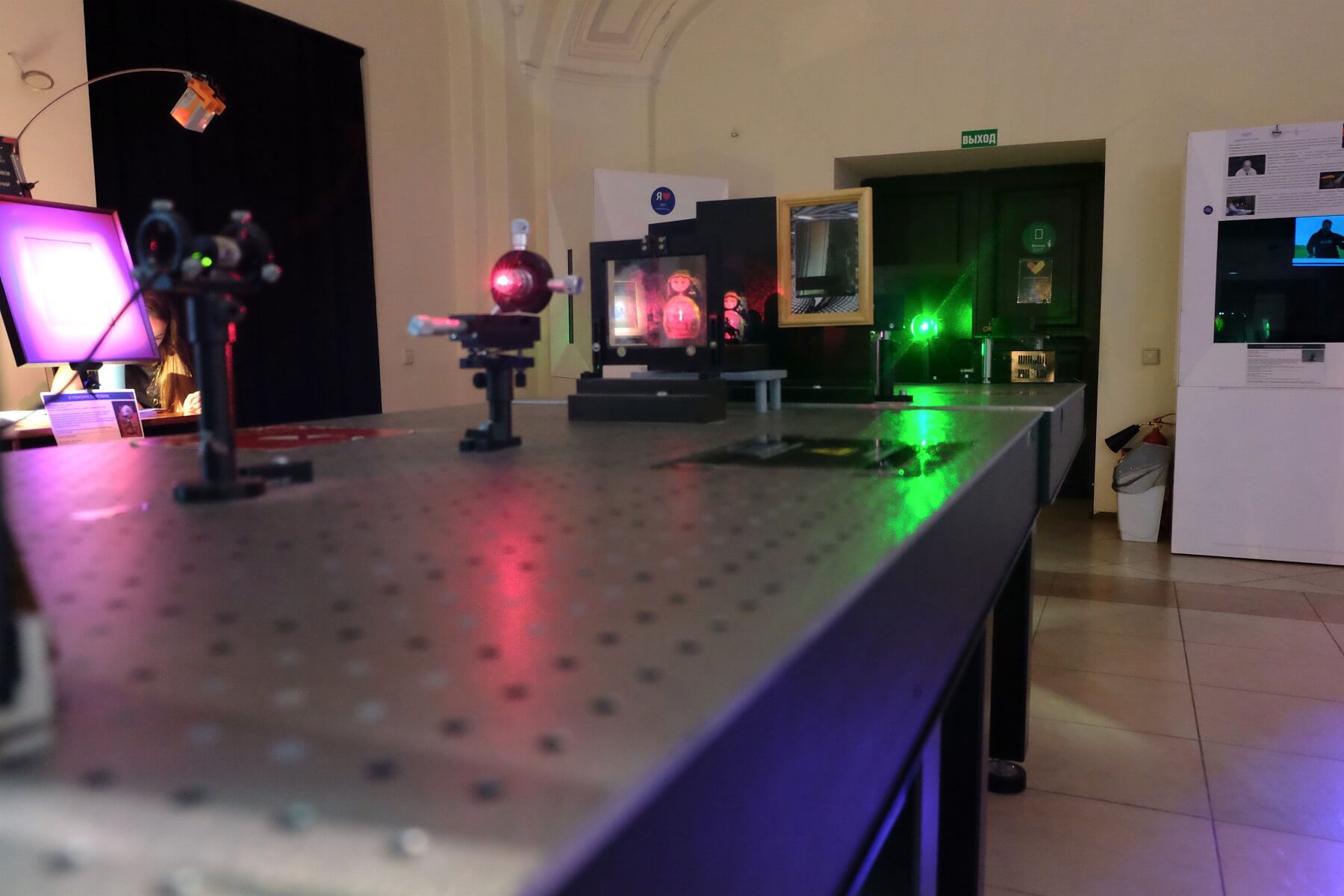

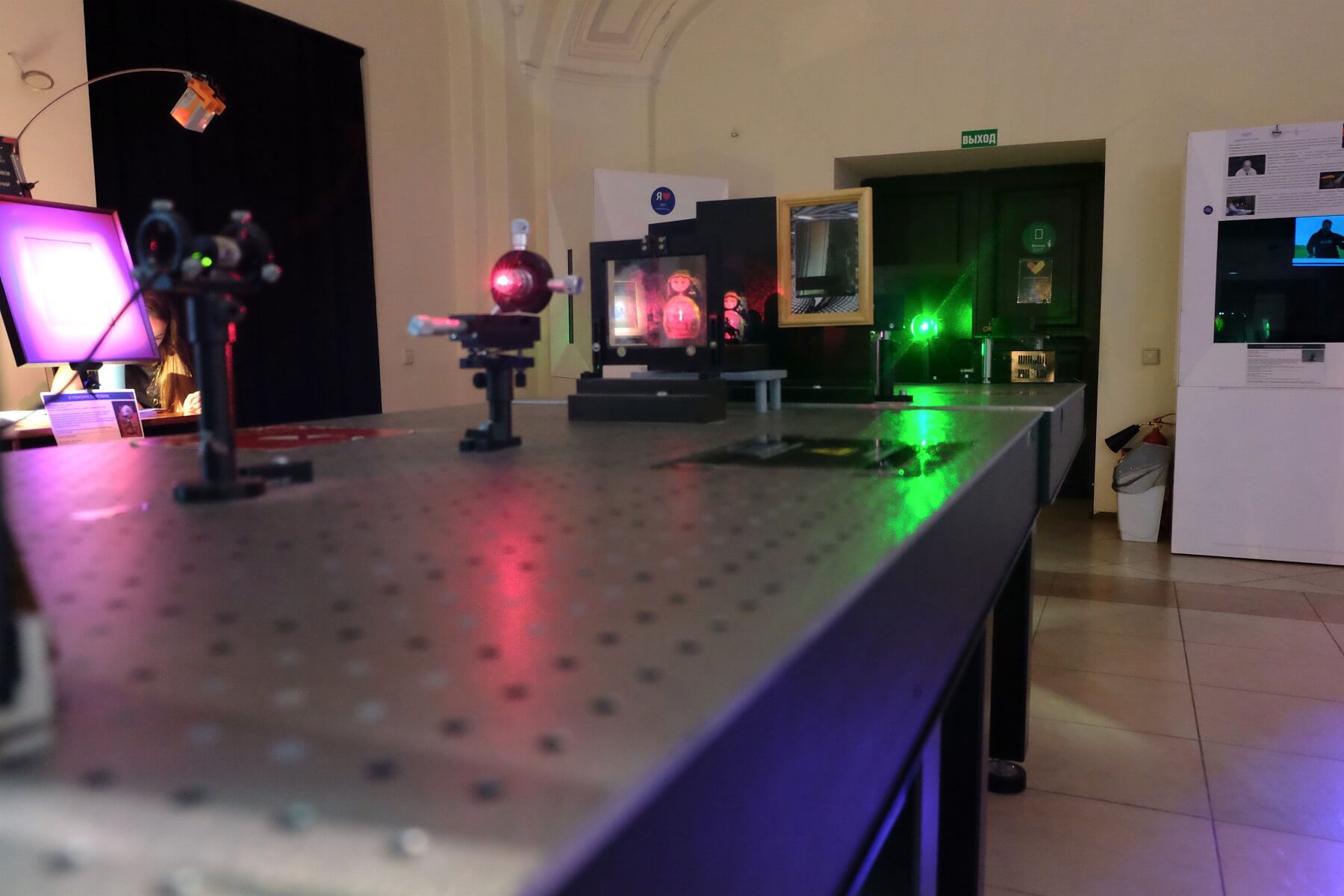

The first half of the exhibition guides the visitors through the history of optics and the modern developments in holographic tech. You can even watch a short film about the science of holography — creating 3D-looking objects using light diffraction. Upon entering the museum, you see two displays illustrating the process of hologram recording — one with a matryoshka, another with a miniature copy of the Bronze Horseman.

The green display showcases the process of recording a transmission hologram, devised in the 1960s by Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks of the University of Michigan.

The red display showcases the competing technique of USSR’s Yuri Denisyuk. Unlike transmission holograms, Denisyuk’s creations can be viewed without a laser — plain white light is sufficient.

Holograms take up a big chunk of the exhibition — which makes sense, given that Denisyuk worked at this particular building when devising his holographic recorder.

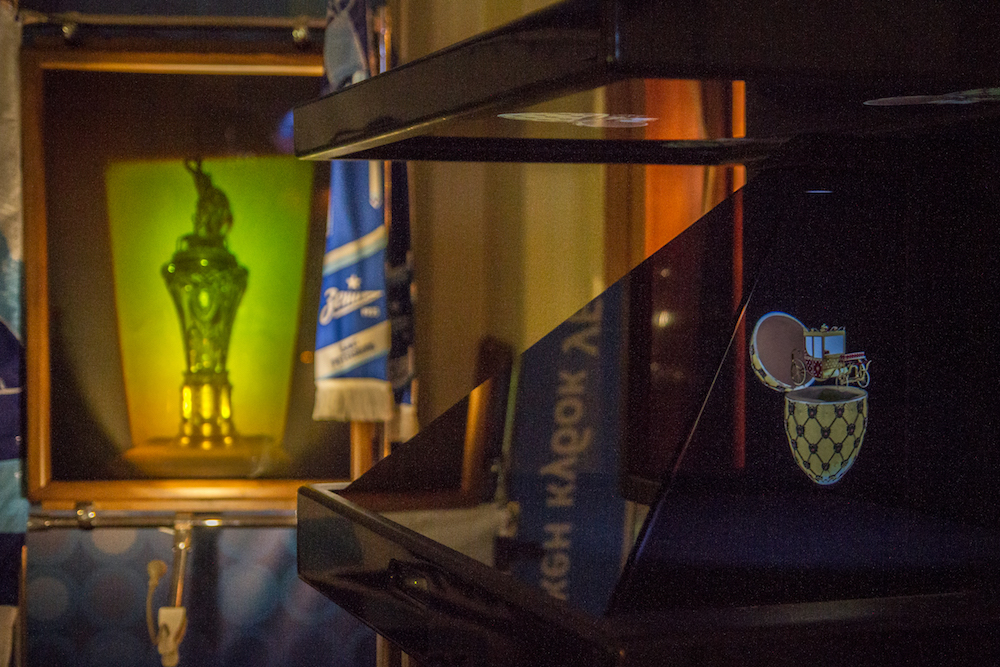

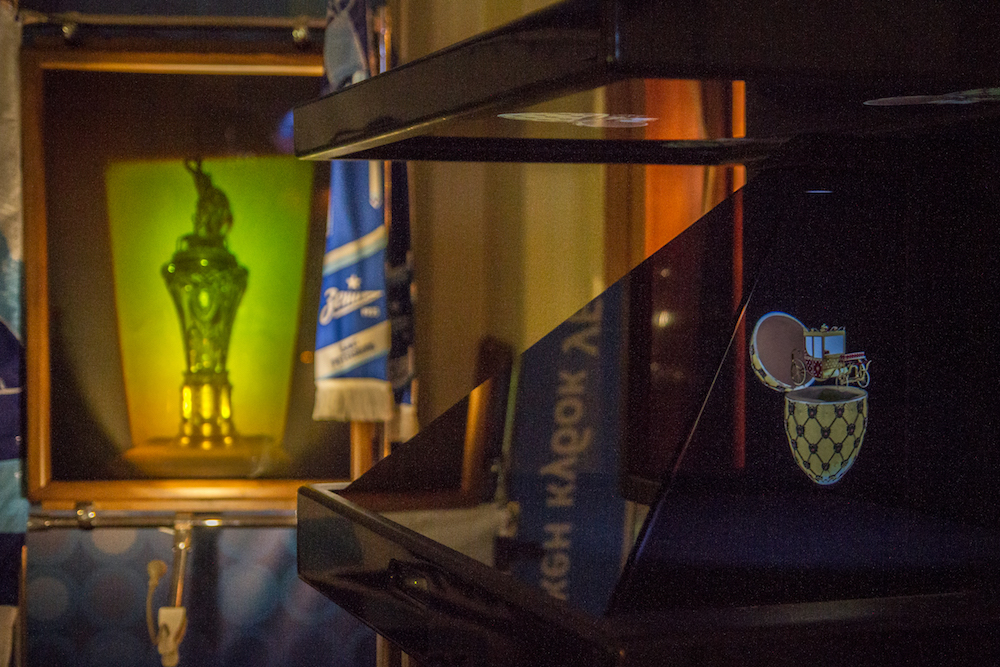

Denisyuk’s holographic technique is widely used to this day, in particular to create optoclones — analogue holograms indistinguishable from real objects. Several optoclones of Faberge eggs and imperial crown jewels can be found on display at the museum.

Pictured: optoclones of “The Caesar’s Ruby”, the medal of the Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky, and the Esclavage Bow

Digital holograms are created with the help of 3D modelling and digital lasers. Photos and videos of the object are used to create its initial virtual render. Then the render is converted into a mathematical lighting model, which guides the laser as it is burns the polymer film. Holograms like these require specialised printers with red, green and blue lasers (here’s a short video demonstration).

Digital holograms can consist of up to four different images, each viewable from an angle of their own. Some holograms’ image changes as you circle them.

Digital holograms have not seen wide adoption thanks to their prohibitive cost. There are no holoprinters in Russia, and the digital holograms in our museum, like the map of Mt. Athos below, were printed in Latvia and the United States.

Pictured: the holographic map of Mt. Athos?

The second room of our museum (pictured below) also contains hologram-related exhibits.

Pictured: the second room with the holograms

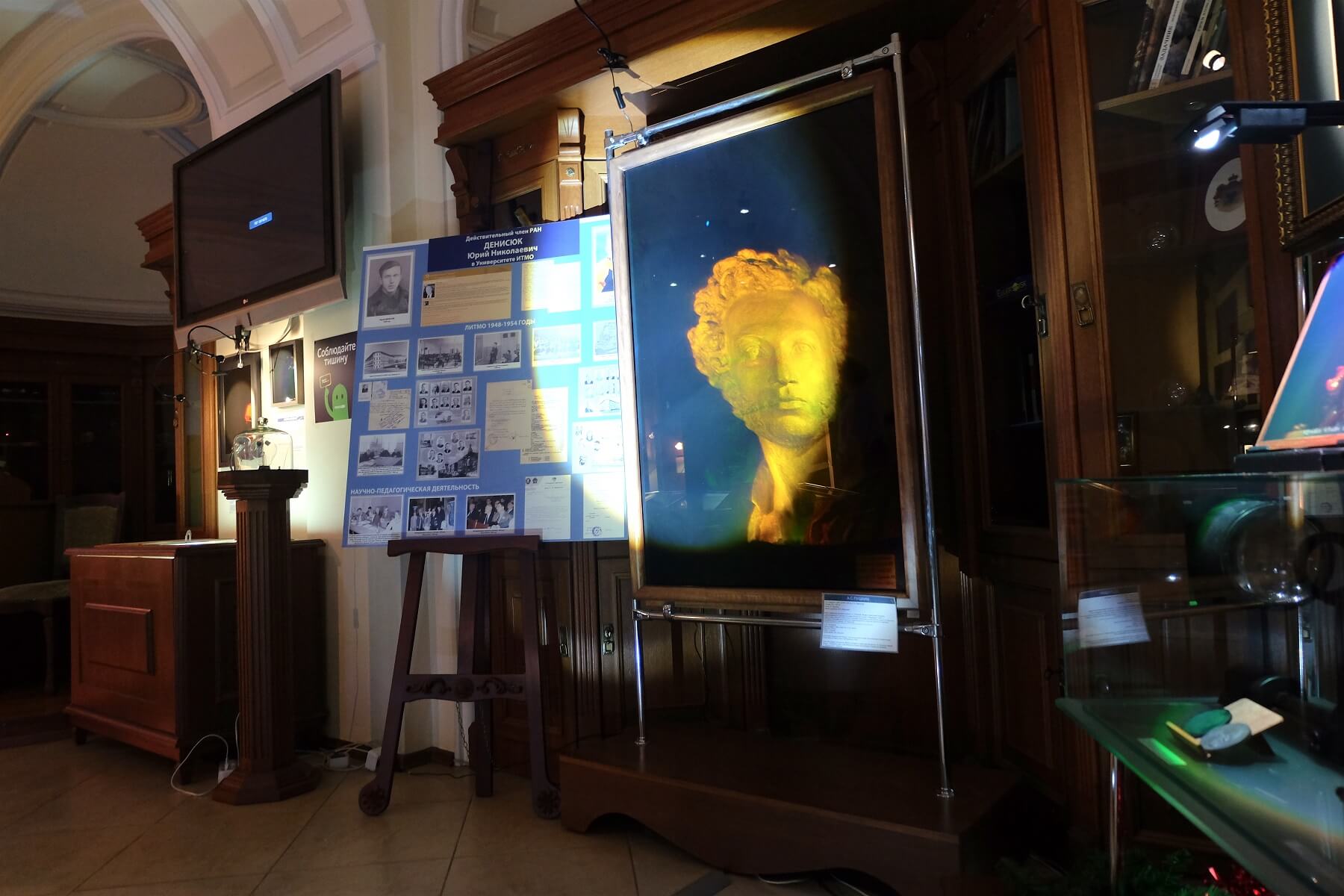

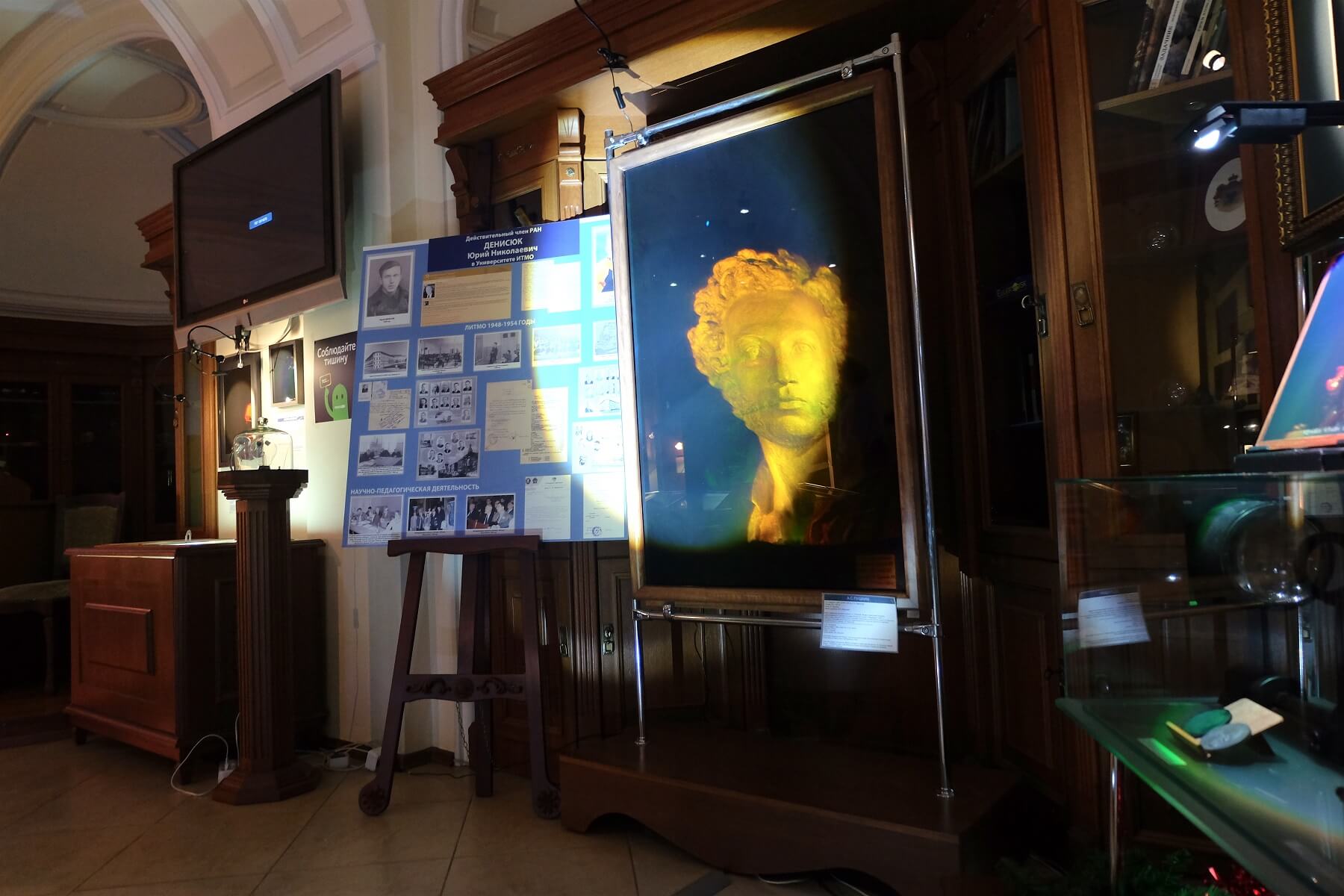

There you can see a holographic portrait of the famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. It is among the biggest glass holograms in our collection, and the biggest analogue hologram on display.

There is also a stand dedicated to the life and work of Yuri Denisuyk, as well as holograms with the scenes from the Hollywood blockbuster “I am Legend”.

You’ll also see holograms of museum pieces from around the world — like this Hotei from the Russian Museum of Ethnography.

To the left of Pushkin’s holographic bust, you’ll see what looks like a lightbulb in a transparent enclosure. It’s the Crookes radiometer — an airtight bulb with a set of blades that rotate when exposed to light.

Radiometer’s blades have two sides: one darker than the other. Darker surfaces are better at absorbing heat from light sources. The tiny temperature difference created by a ray of light forces the gas particles inside the bulb to bounce off the blades’ warmer side, creating motion.

Many different optical gadgets are on display: from microscopes and “reading stones” to vintage cameras and perscription glasses. You can learn all about the history of mirrors, starting with the Aztec obsidian experiments, and ending with hand-crafted 17th century Venetian glass.

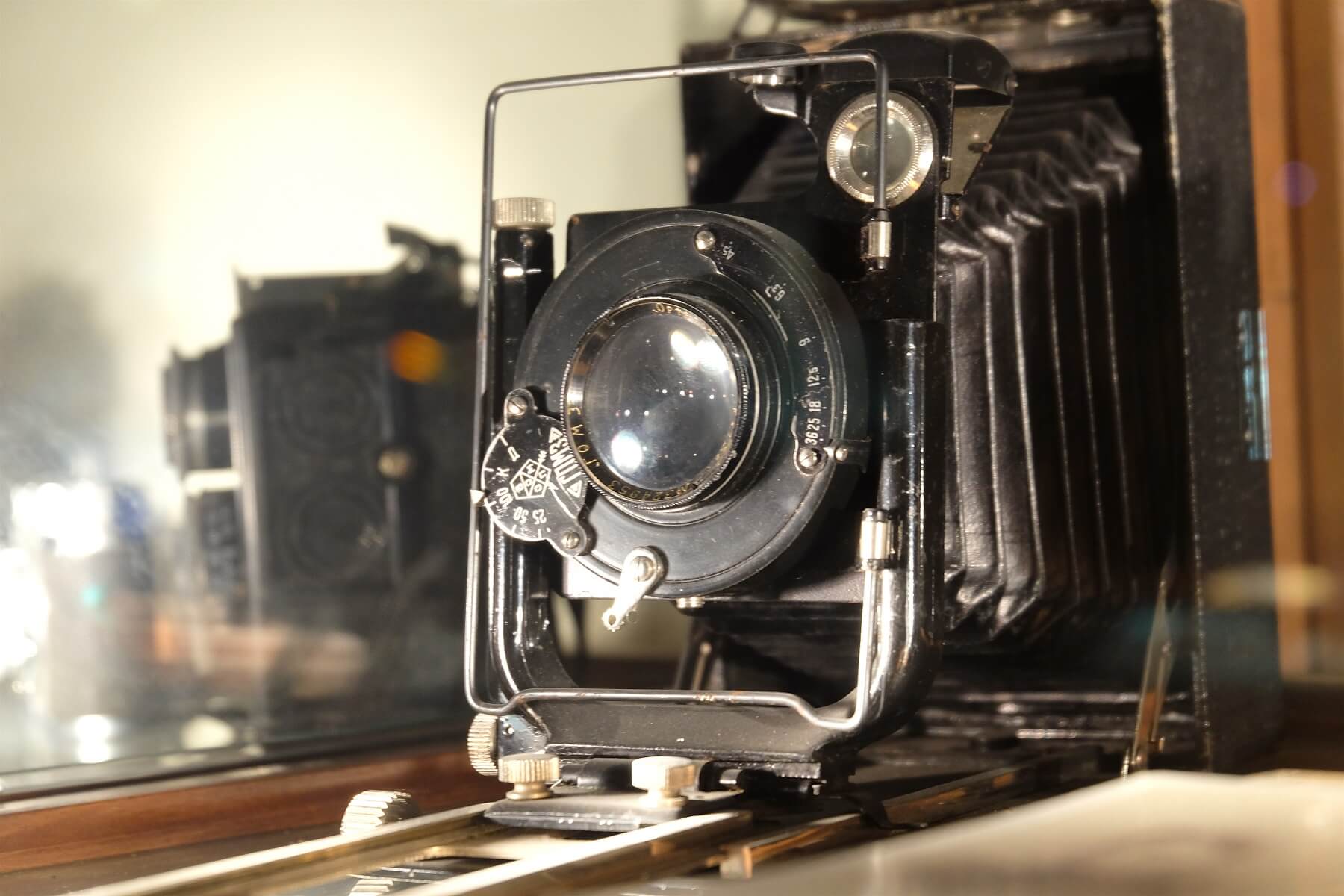

Our camera collection tells the story of photography from camerae obscurae to modern SLRs.

Pictured: our camera collection

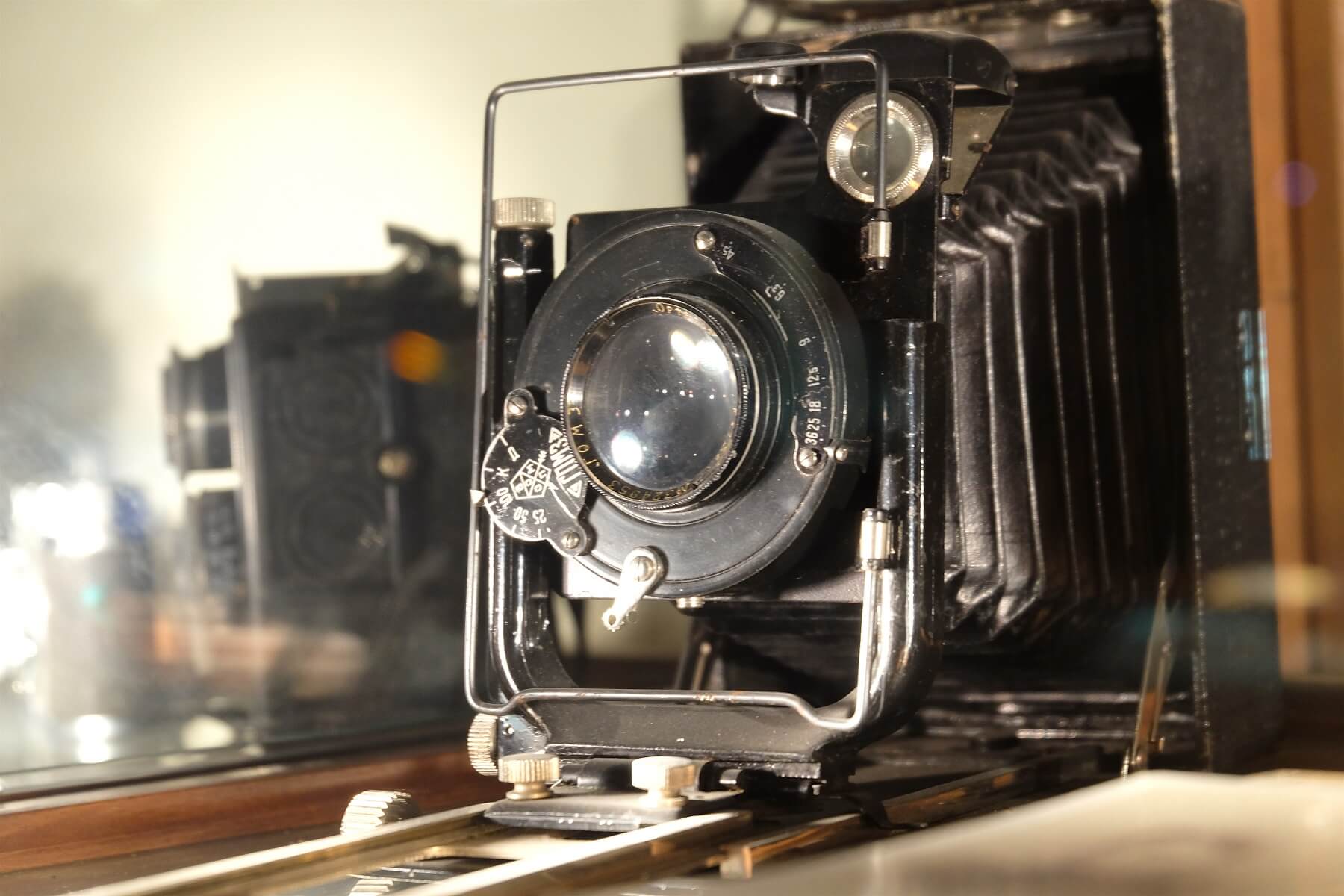

It includes a number of curious folding cameras — the French WW2-era Pontiac MFAP, the German AGFA Billy Record from the 1920s, and the first widely available Soviet-built camera — the Fotokor.

Pictured: the “Fotokor” folding film camera»

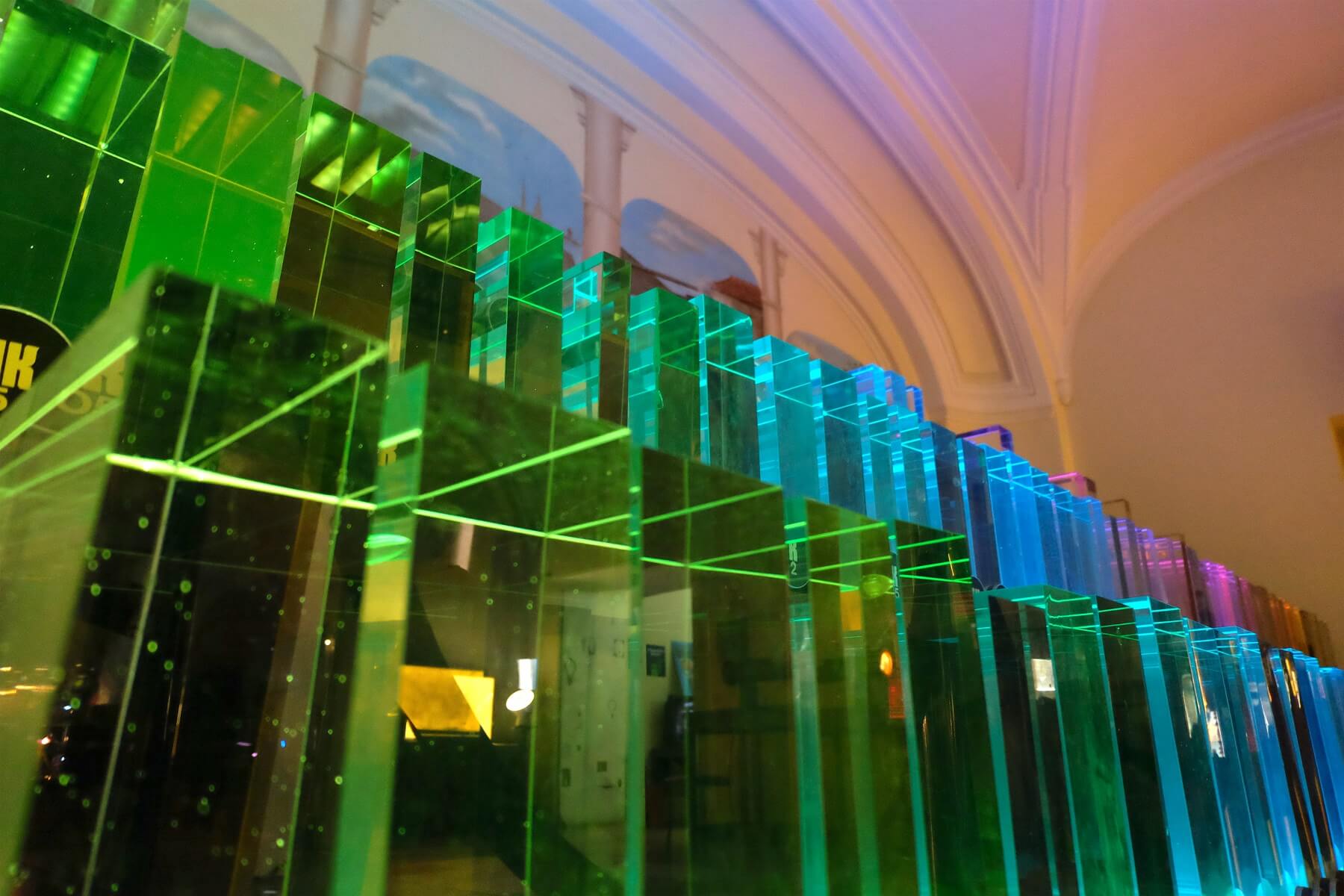

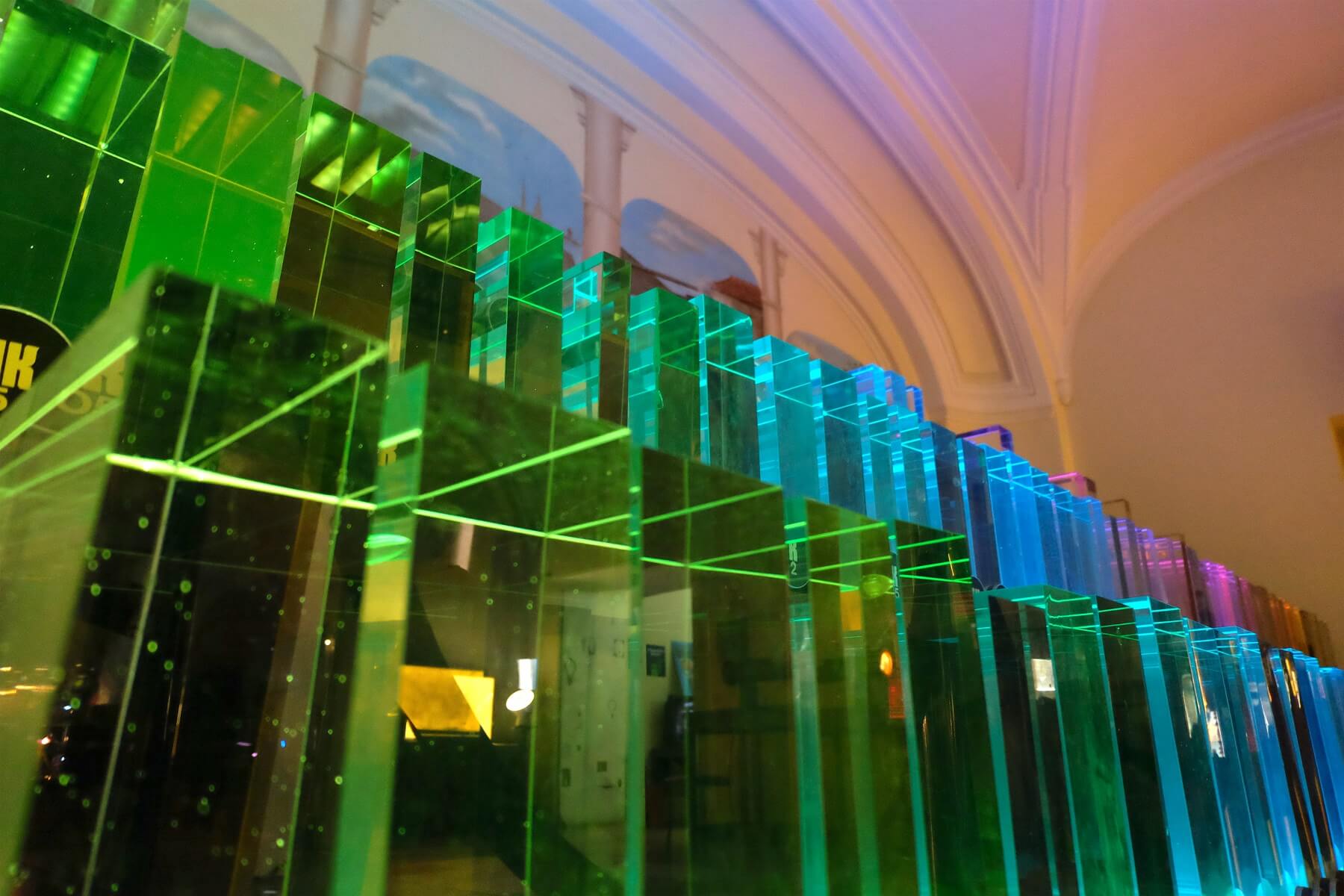

The following room houses an organ-like structure with “pipes” made from 144 different kinds of glass. Diversity-wise or size-wise, no other place on Earth has a collection like this. Its assembly begun in the communist era as a way to commemorate the successful development of radiation-resistant glass.

The slabs of glass are lit by LED strips. They are connected to a microcontroller that is capable of adjusting their colour and brightness. When a nearby PC plays back a piece of music, the ‘organ’ visualises it, reflecting the pitch and tonality of the work with its lighting. There are 8 visualising algorithms to pick from.

Here’s a video demonstration.

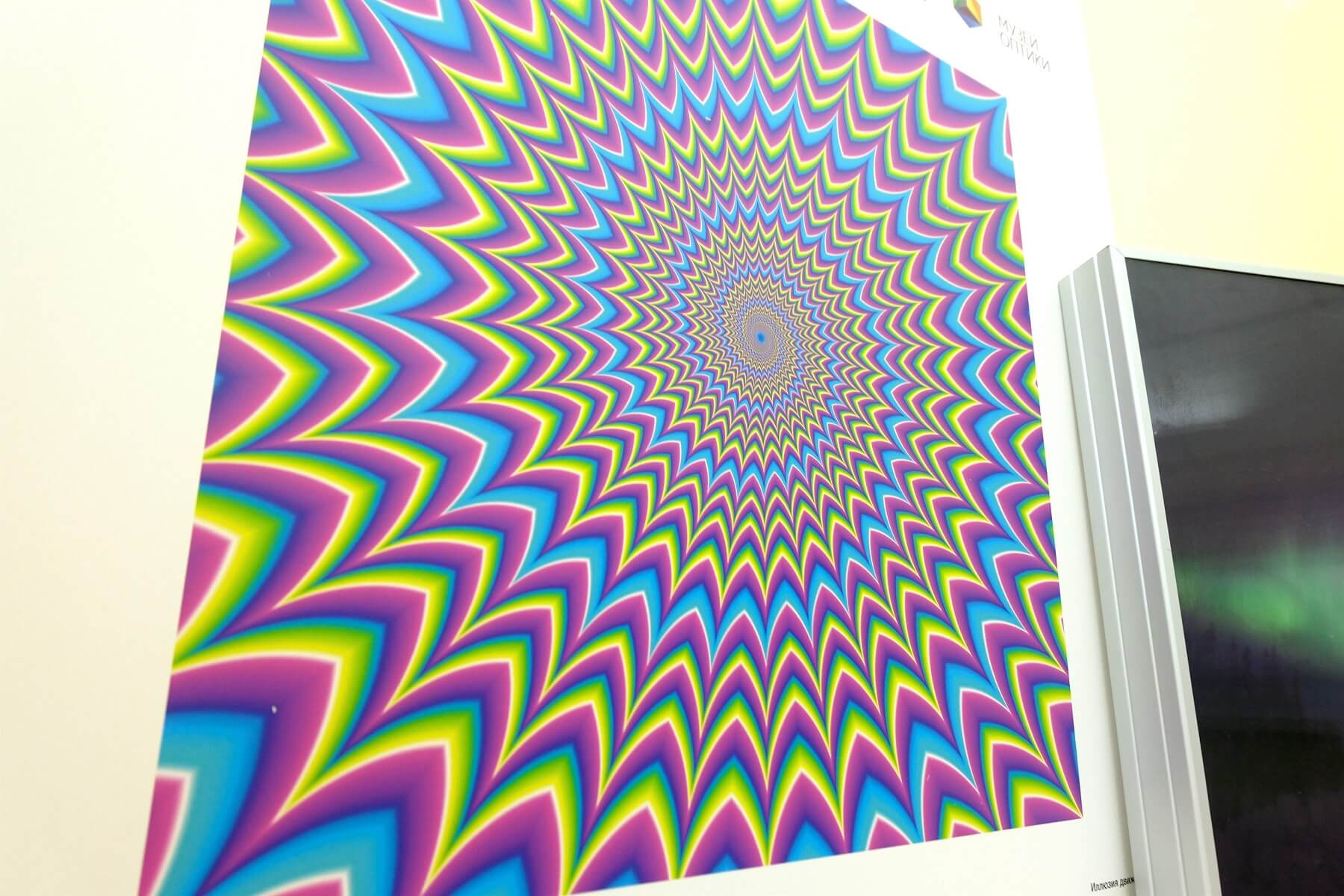

The next part of the exhibition is interactive and very much hands-on. It starts with exhibits related to the history of cinema and 3D visuals. Zoetropes, Phenakistiscopes, Phonotropes helped early modern scientists tackle the subject of human vision, and provided insights into how people make sense of visual information. Phonotropes (pictured below) trick us into thinking that we’re looking at a moving picture thanks to the principle called the visual inertia. If you point a camera at the device, you’ll see all the details your eyes miss.

Pictured: Phonotrope — the modern take on the Zoetrope

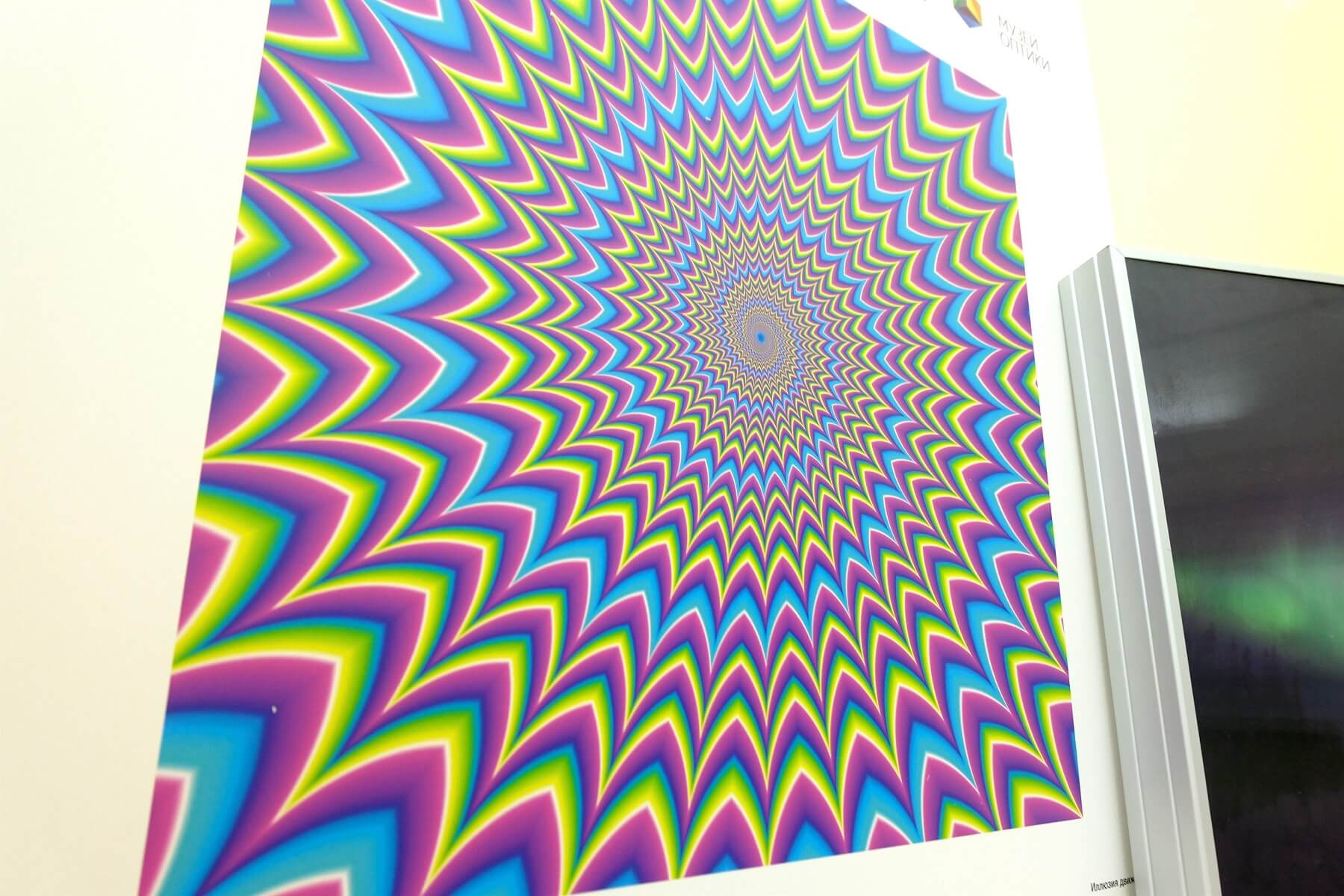

Pictured: an optical illusion

The gimmick behind modern 3D films’ illusion of depth was first discovered in the 19th century. You can look through our vintage stereoscope to see the effect for yourself. Next to the old stereoscope is a glasses-free 3D screen — the latest in 3D technology.

Pictured: a stereoscope from 1901

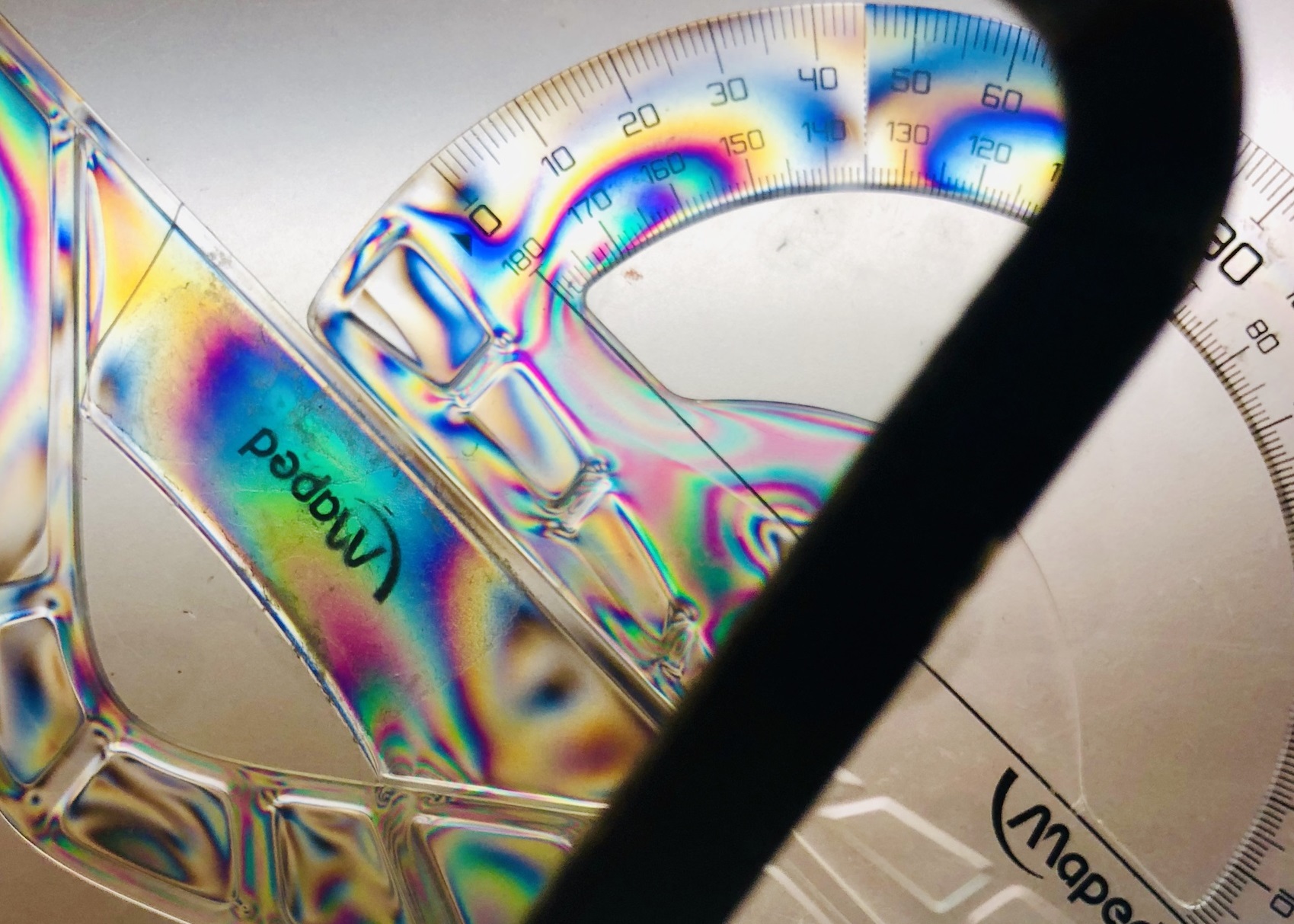

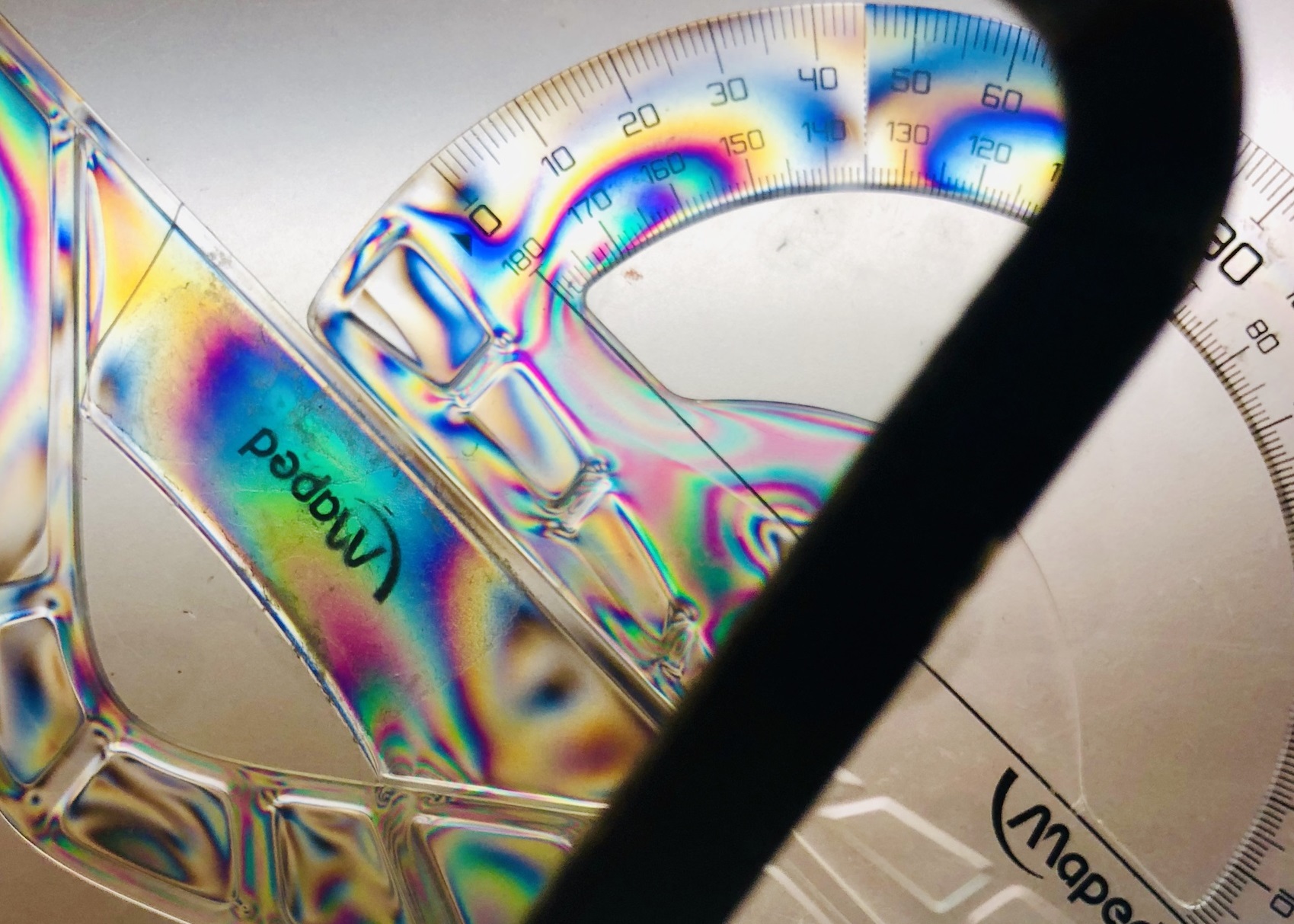

Next up is our collection of photoelastic objects. They look transparent to the naked eye, but start bursting with colour when looked through a special filter.

Photoelasticity manifests itself when you stress a substance so much, it starts refracting light twice. Apart from being a cool party trick, it is a useful indicator when stress-testing bridges or implants.

Pictured below — another seemingly white screen. If looked at through a special filter, you can see the picture of a colourful dragon.

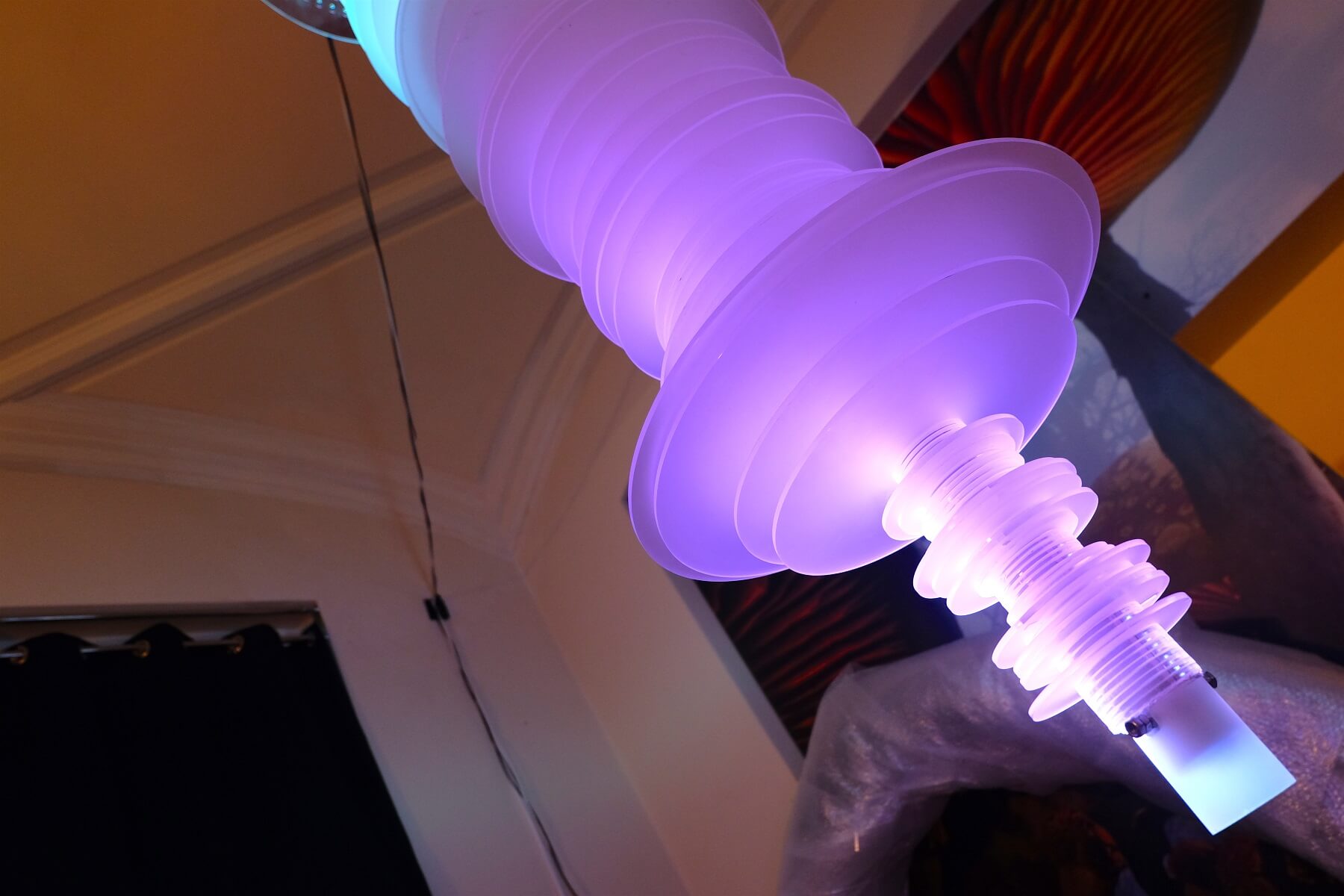

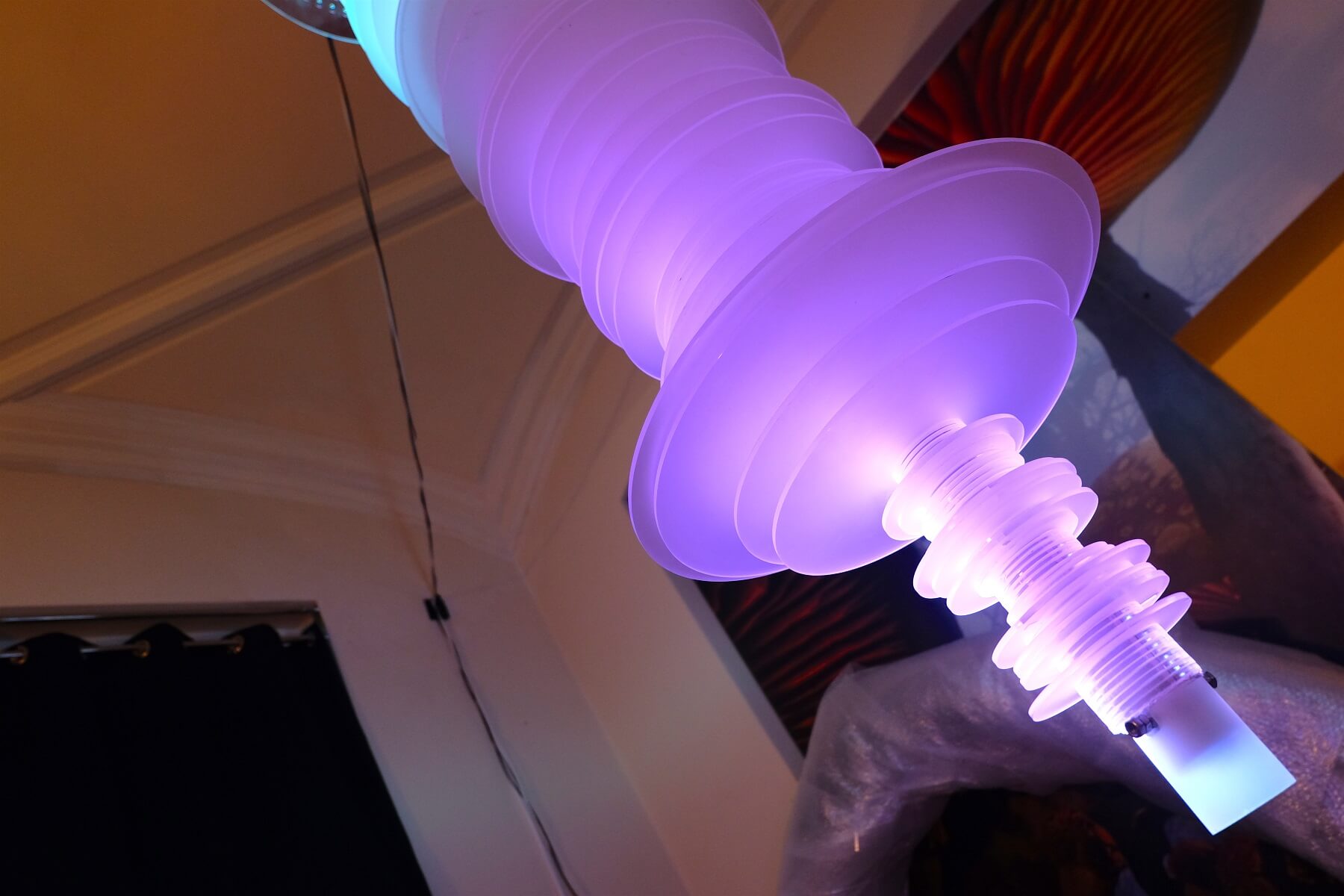

ITMO University staff often works alongside artists to create artwork for the museum. For example, the “Wave” LED installation was created in collaboration with the Sonicology project, headed by the media artist and composer Taras Mashtalir.

The “Wave” is a two-meter-long sculpture fitted with technology that registers the visitors’ movements and generates audio-visual responses.

Pictured: the “Wave” LED installation

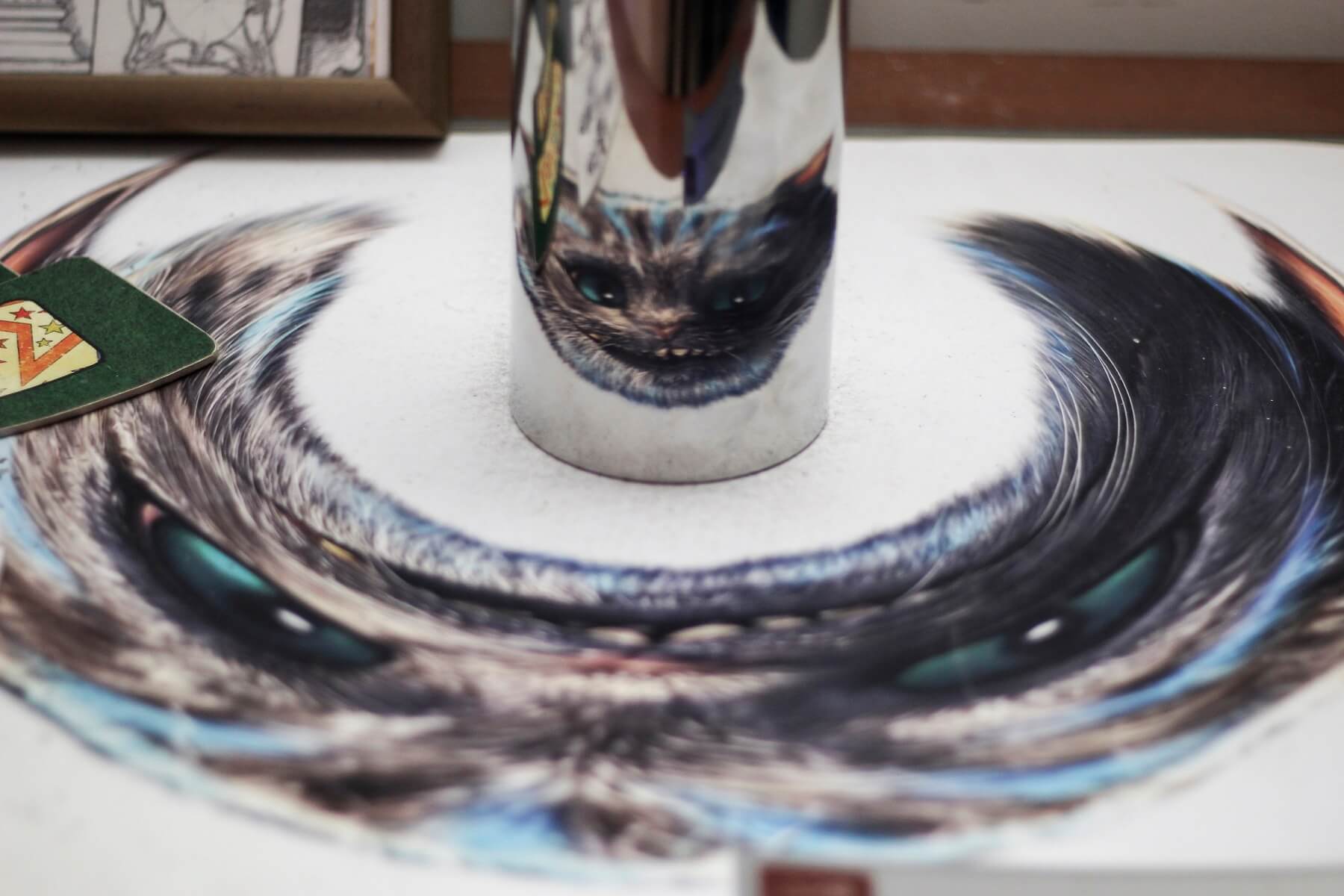

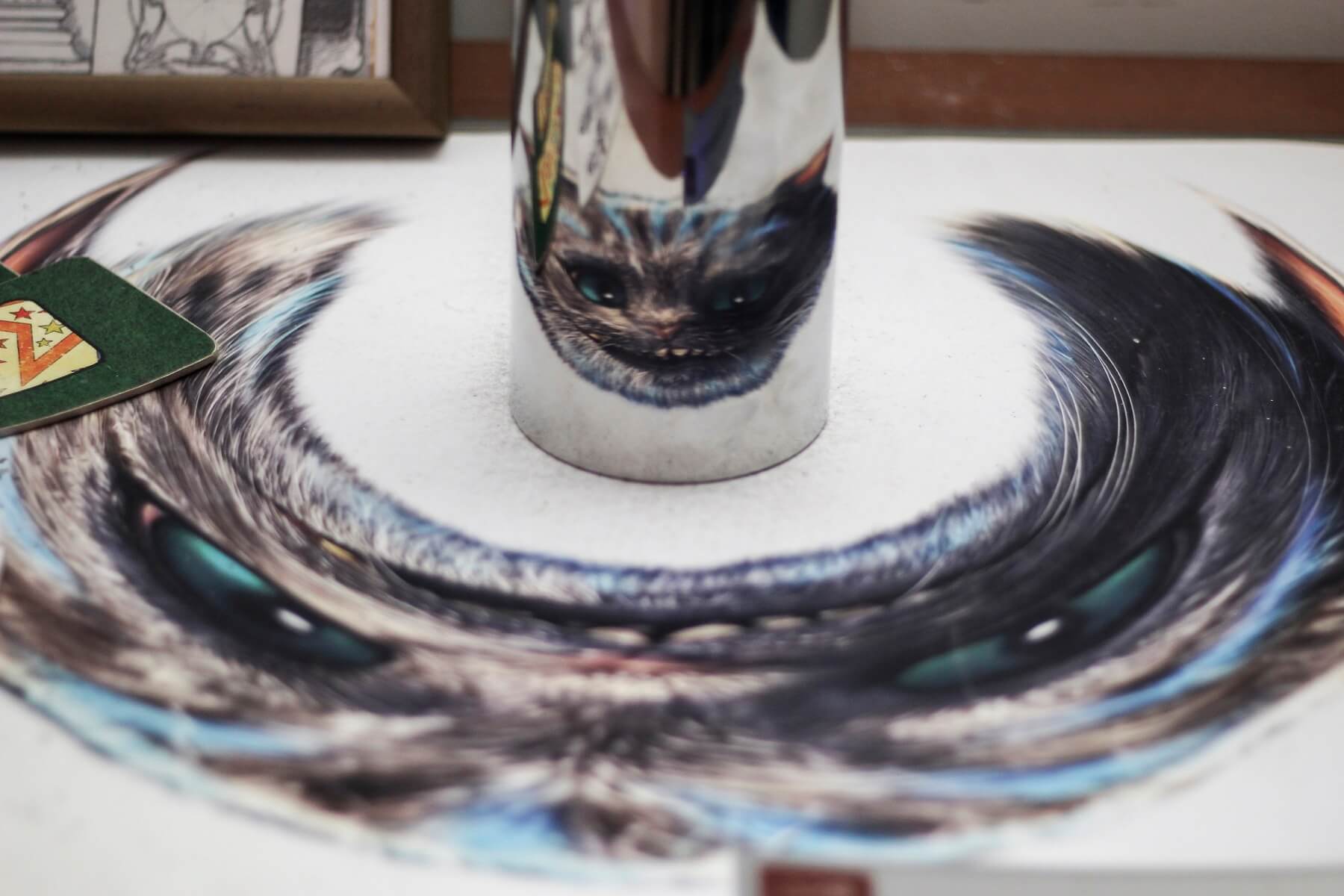

The next room houses the museum’s collection of mirror-based optical illusions. Some of these objects take advantage of anamorphosis to “flatten” images with skewed perspectives.

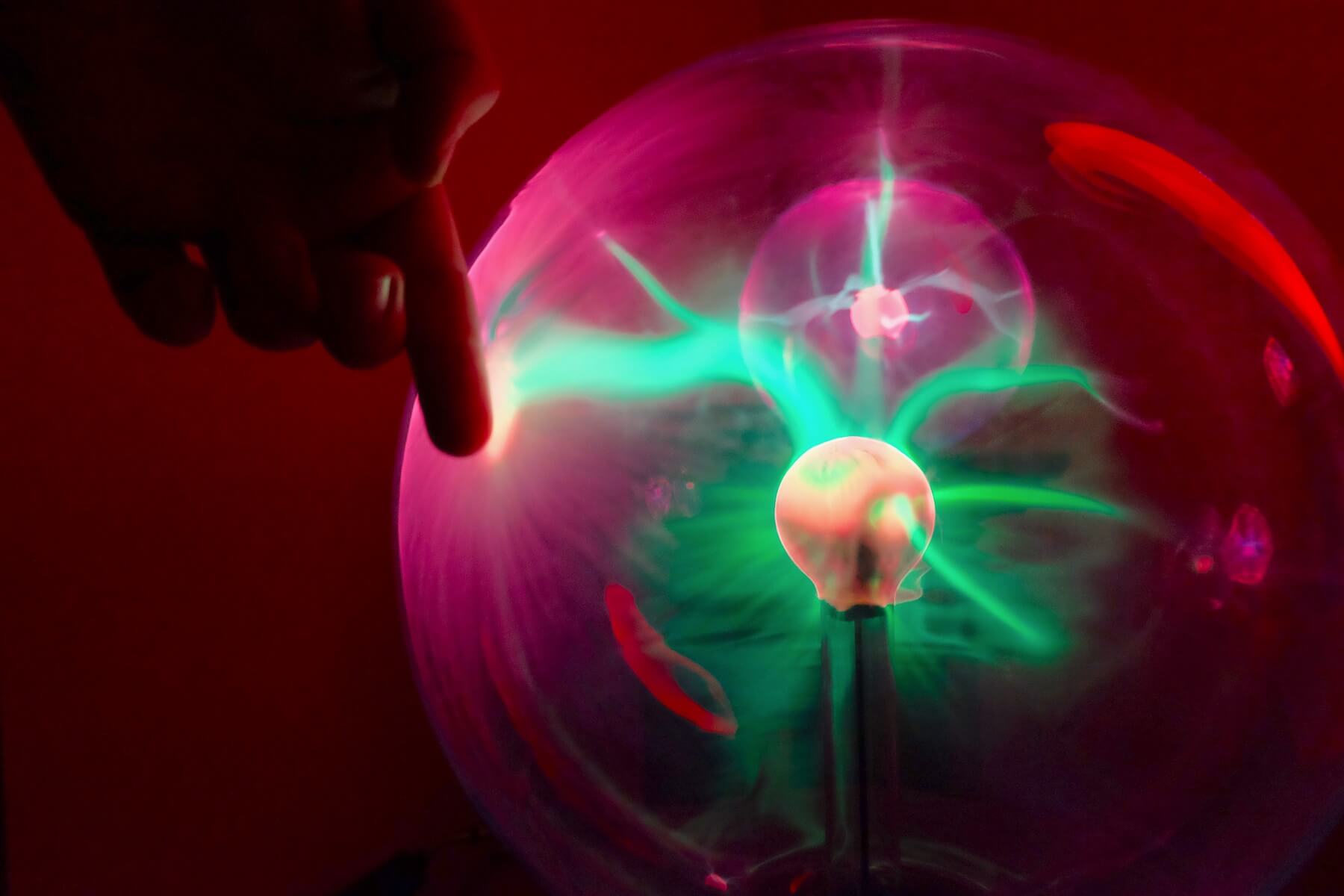

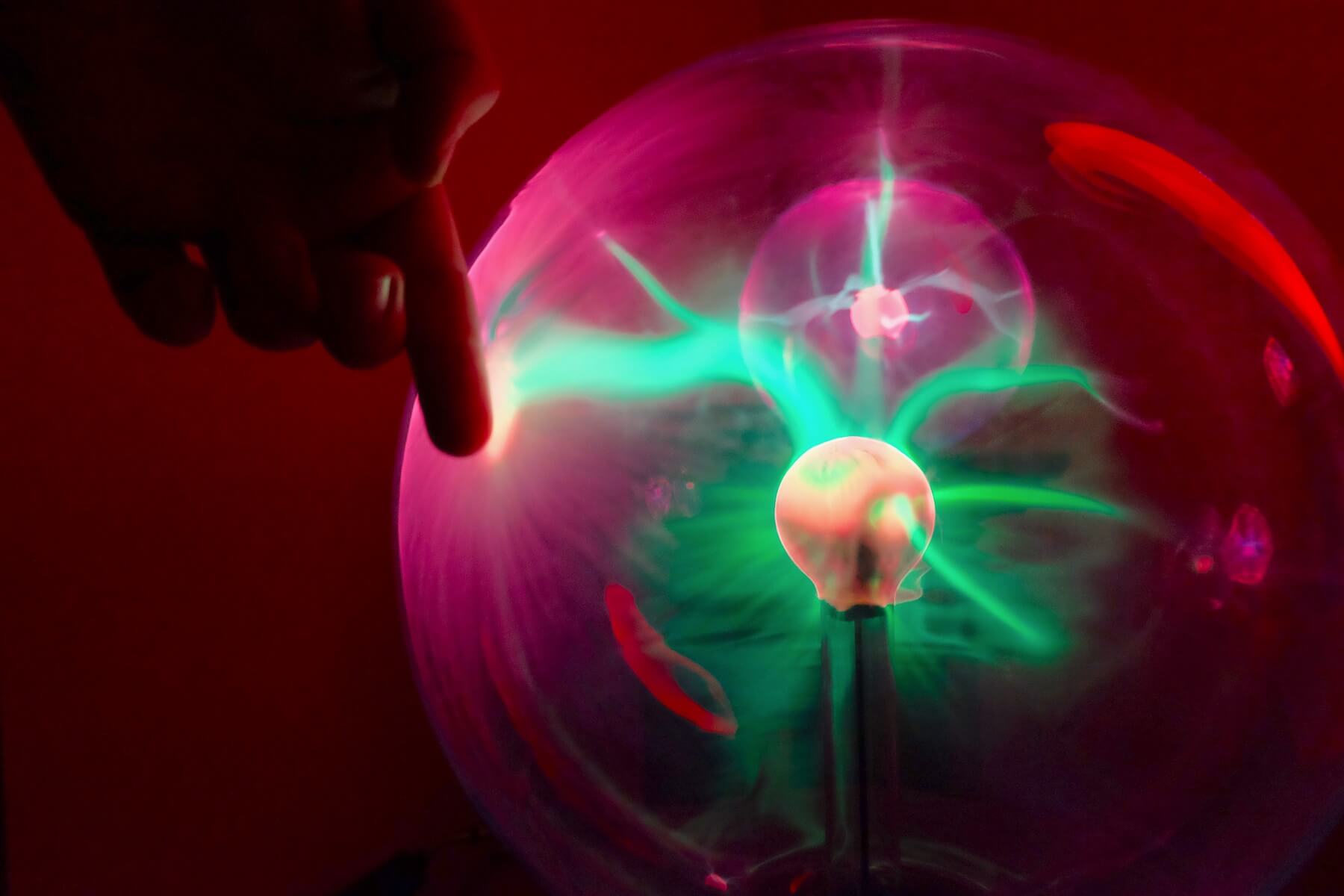

The next room showcases the museum’s collection of plasma lamps. The visitors are free to touch them.

To the right of the wall of lamps is a special light-absorbing surface. You can draw on it with a flashlight. It faces a light-reflecting surface on the other side of the room. If you were to take its picture with a flash, the end result would be dark and poorly lit — the opposite of the desired effect.

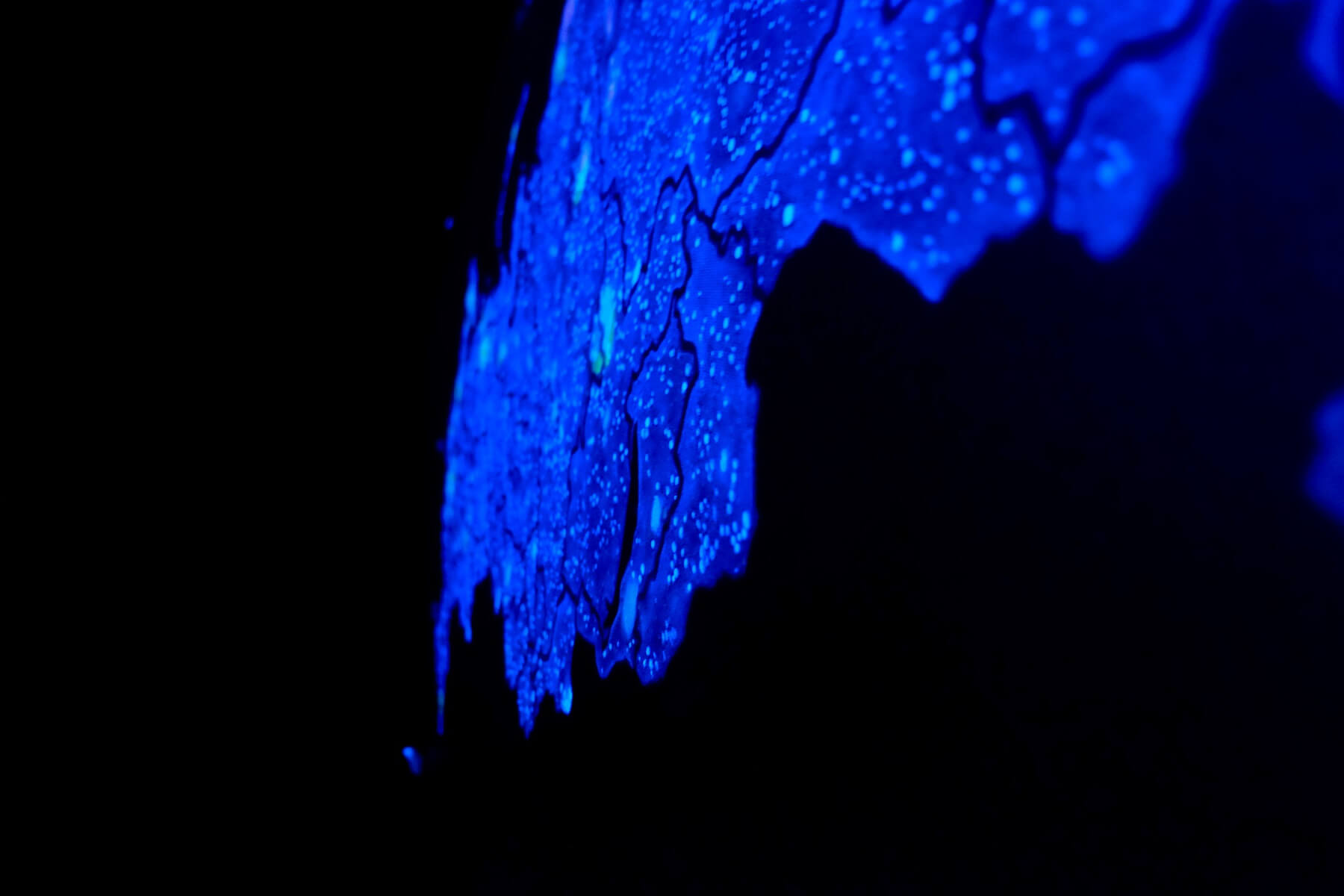

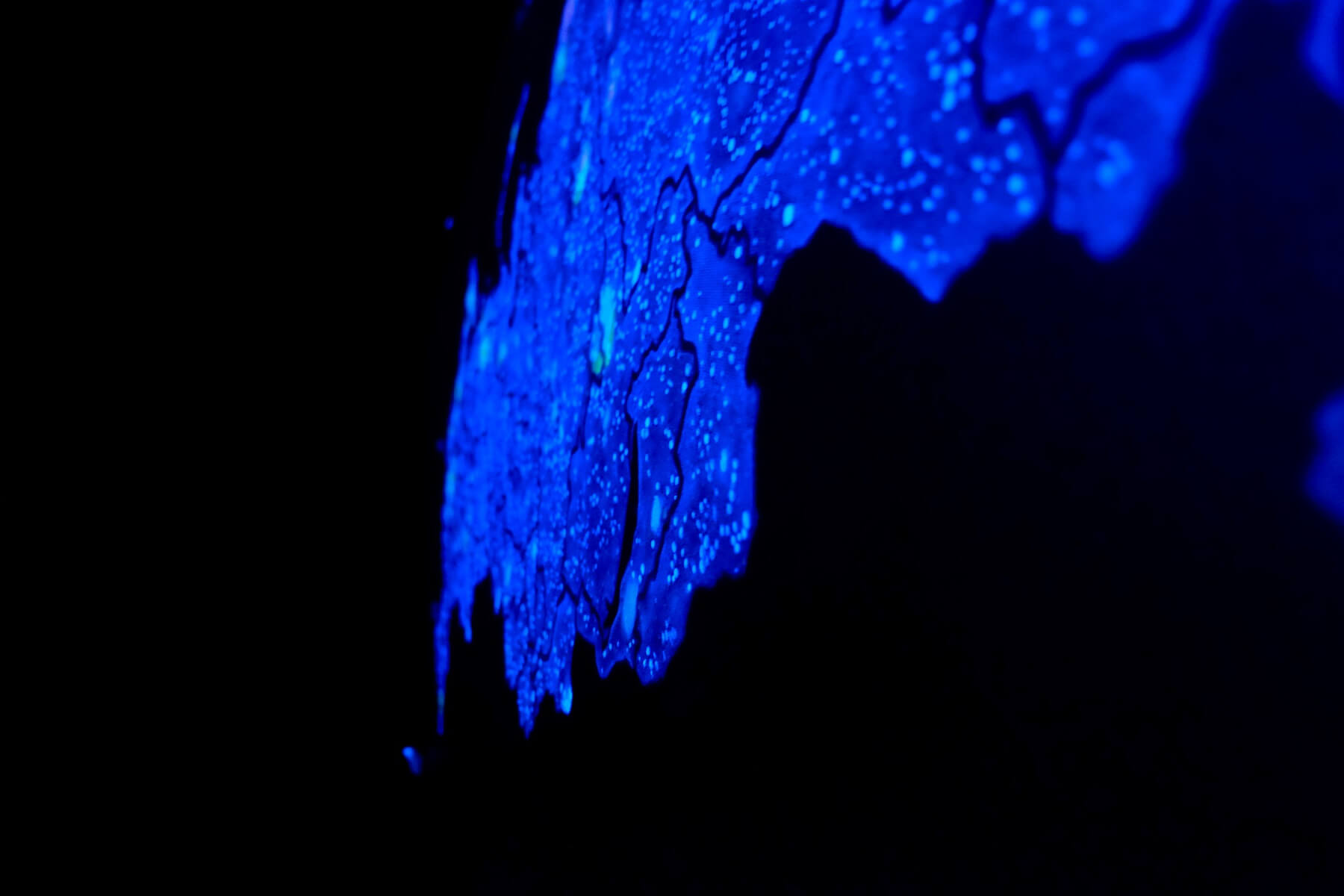

The penultimate room of the museum is dark and filled with luminescent objects, like the glowing map of Russia.

Pictured: a luminescent map of Russia

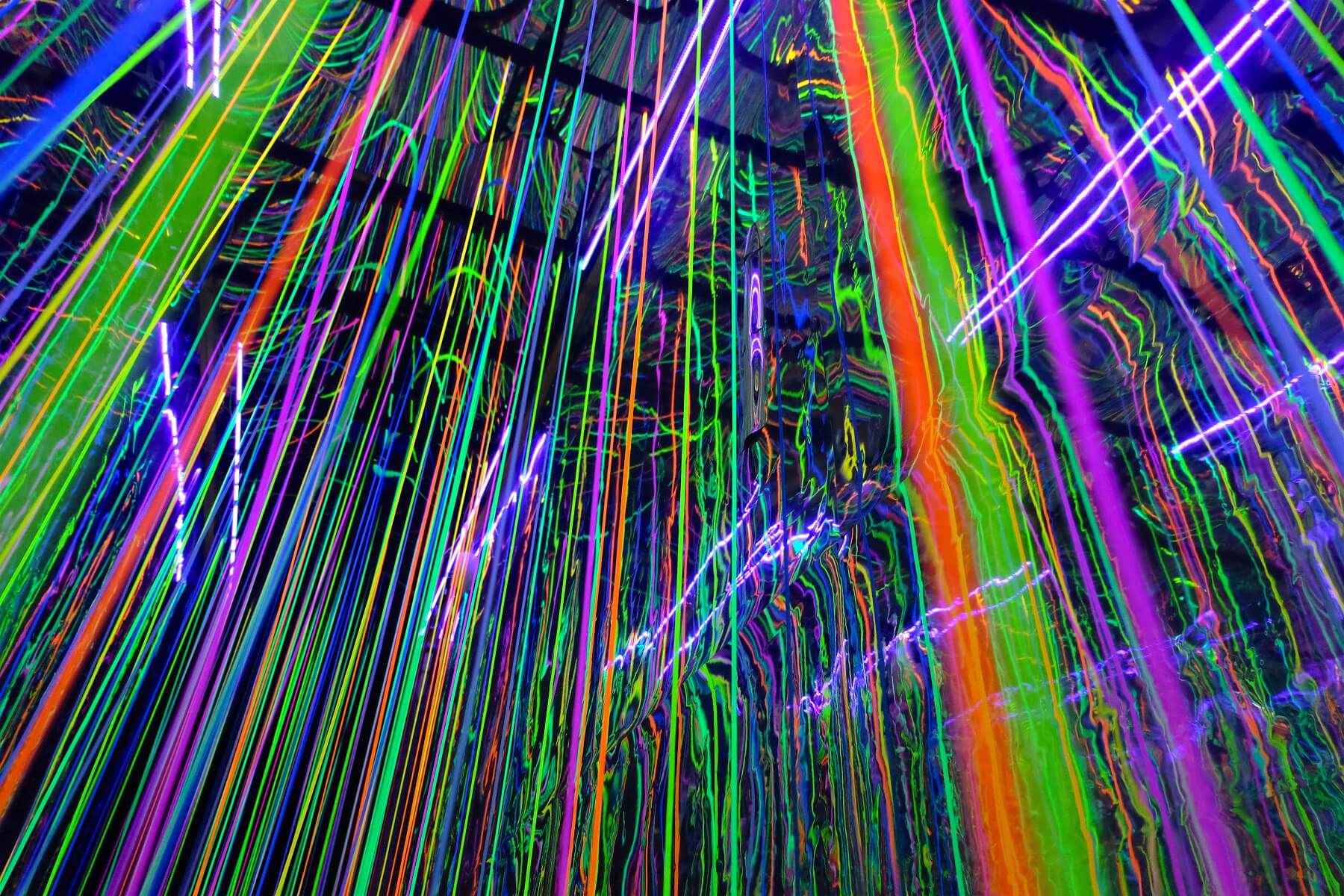

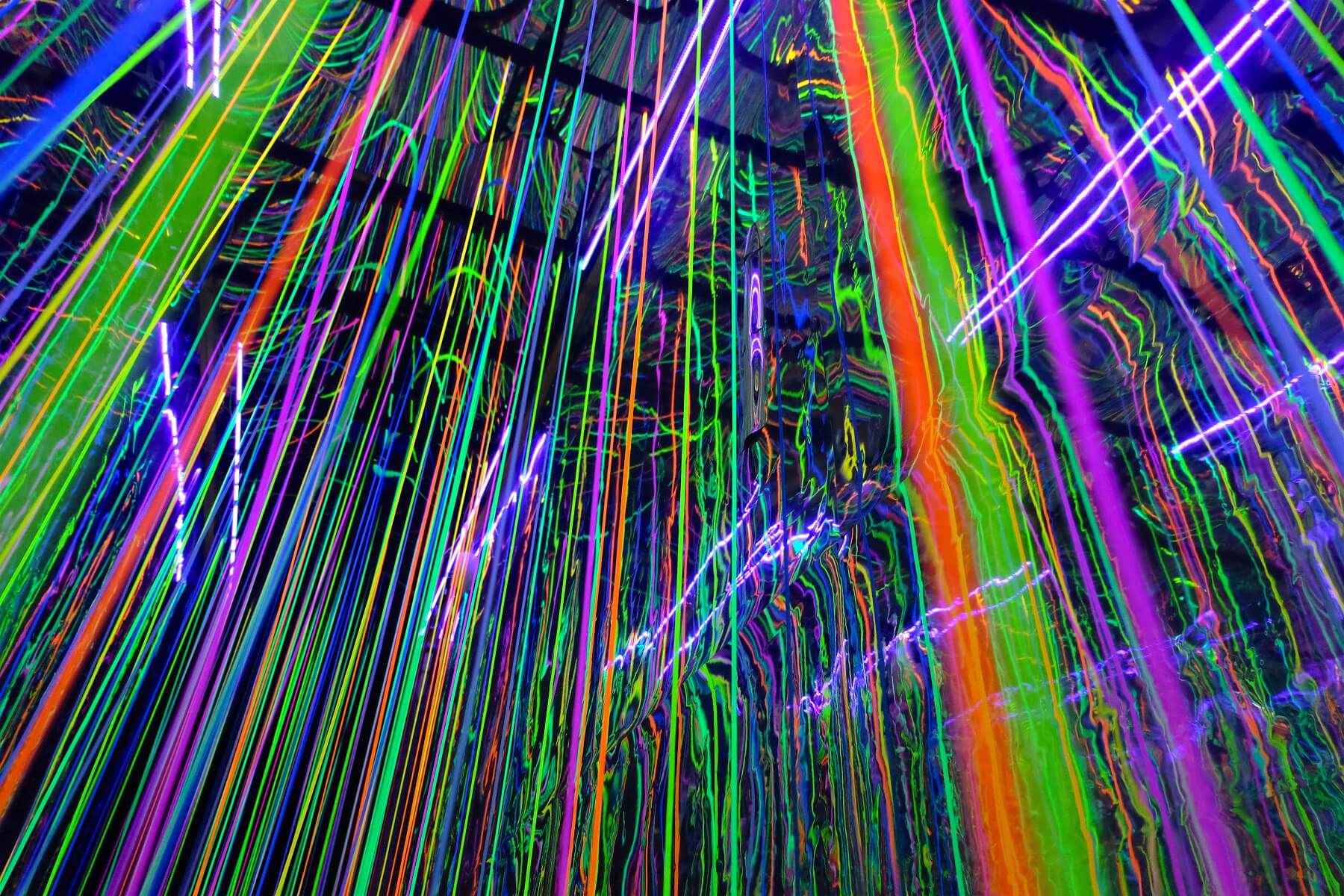

The last exhibit is called “The Magic Forest”. It is an art object made of mirrors and luminescent threads.

Pictured: the “Magic Forest”

Every day our staff is working on new exhibits and improving the existing ones. A new guided tour starts every 20 minutes. We host a special series of workshops for schoolkids that explains high school optics.

In the near future we’ll be increasing the number of interactive exhibits, talks and workshops. There’s going to be a VR zone with virtual exhibits from the university’s Video 360 Project, as well as artists from around the world. We hope our museum will continue to inspire curiosity in its visitors.

Further reading:

Bandwidth warning: lots of photos below!

A bit of history

The museum of optics is located in the former building of the Vavilov State Optical Institute on Vasilevskiy Island. In 2007, when the historic neighbourhood behind the old Stock Exchange was being renovated, the institute’s staff had to decide the building’s fate. That’s when, inspired by the growing edutainment movement, Sergei Stafeev of the physics and engineering department proposed the idea of the museum.

The museum was initially designed to promote the study of optics, and showcase the potential of the field to those who’re yet to choose a career. For the first few years, it was closed to the general public and could only be visited by guided school groups. 2015 saw the opening of the Magic of Light permanent exhibition — an interactive pop-sci journey into optics spread over 10 thousand square feet of space.

With it, the museum started operating regular hours and welcoming solo visitors.

The educational half

The first half of the exhibition guides the visitors through the history of optics and the modern developments in holographic tech. You can even watch a short film about the science of holography — creating 3D-looking objects using light diffraction. Upon entering the museum, you see two displays illustrating the process of hologram recording — one with a matryoshka, another with a miniature copy of the Bronze Horseman.

The green display showcases the process of recording a transmission hologram, devised in the 1960s by Emmett Leith and Juris Upatnieks of the University of Michigan.

The red display showcases the competing technique of USSR’s Yuri Denisyuk. Unlike transmission holograms, Denisyuk’s creations can be viewed without a laser — plain white light is sufficient.

Holograms take up a big chunk of the exhibition — which makes sense, given that Denisyuk worked at this particular building when devising his holographic recorder.

Denisyuk’s holographic technique is widely used to this day, in particular to create optoclones — analogue holograms indistinguishable from real objects. Several optoclones of Faberge eggs and imperial crown jewels can be found on display at the museum.

Pictured: optoclones of “The Caesar’s Ruby”, the medal of the Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky, and the Esclavage Bow

Digital holograms are created with the help of 3D modelling and digital lasers. Photos and videos of the object are used to create its initial virtual render. Then the render is converted into a mathematical lighting model, which guides the laser as it is burns the polymer film. Holograms like these require specialised printers with red, green and blue lasers (here’s a short video demonstration).

Among the museum’s digital holograms, created by university staff, are models of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra and the Kronstadt Naval Cathedral.

Digital holograms can consist of up to four different images, each viewable from an angle of their own. Some holograms’ image changes as you circle them.

Digital holograms have not seen wide adoption thanks to their prohibitive cost. There are no holoprinters in Russia, and the digital holograms in our museum, like the map of Mt. Athos below, were printed in Latvia and the United States.

Pictured: the holographic map of Mt. Athos?

The second room of our museum (pictured below) also contains hologram-related exhibits.

Pictured: the second room with the holograms

There you can see a holographic portrait of the famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. It is among the biggest glass holograms in our collection, and the biggest analogue hologram on display.

There is also a stand dedicated to the life and work of Yuri Denisuyk, as well as holograms with the scenes from the Hollywood blockbuster “I am Legend”.

You’ll also see holograms of museum pieces from around the world — like this Hotei from the Russian Museum of Ethnography.

To the left of Pushkin’s holographic bust, you’ll see what looks like a lightbulb in a transparent enclosure. It’s the Crookes radiometer — an airtight bulb with a set of blades that rotate when exposed to light.

Radiometer’s blades have two sides: one darker than the other. Darker surfaces are better at absorbing heat from light sources. The tiny temperature difference created by a ray of light forces the gas particles inside the bulb to bounce off the blades’ warmer side, creating motion.

A big section of this room is dedicated to the history of optics: the development of photography, prescription glasses and lamps.

Many different optical gadgets are on display: from microscopes and “reading stones” to vintage cameras and perscription glasses. You can learn all about the history of mirrors, starting with the Aztec obsidian experiments, and ending with hand-crafted 17th century Venetian glass.

Our camera collection tells the story of photography from camerae obscurae to modern SLRs.

Pictured: our camera collection

It includes a number of curious folding cameras — the French WW2-era Pontiac MFAP, the German AGFA Billy Record from the 1920s, and the first widely available Soviet-built camera — the Fotokor.

Pictured: the “Fotokor” folding film camera»

The following room houses an organ-like structure with “pipes” made from 144 different kinds of glass. Diversity-wise or size-wise, no other place on Earth has a collection like this. Its assembly begun in the communist era as a way to commemorate the successful development of radiation-resistant glass.

The slabs of glass are lit by LED strips. They are connected to a microcontroller that is capable of adjusting their colour and brightness. When a nearby PC plays back a piece of music, the ‘organ’ visualises it, reflecting the pitch and tonality of the work with its lighting. There are 8 visualising algorithms to pick from.

Here’s a video demonstration.

The interactive half

The next part of the exhibition is interactive and very much hands-on. It starts with exhibits related to the history of cinema and 3D visuals. Zoetropes, Phenakistiscopes, Phonotropes helped early modern scientists tackle the subject of human vision, and provided insights into how people make sense of visual information. Phonotropes (pictured below) trick us into thinking that we’re looking at a moving picture thanks to the principle called the visual inertia. If you point a camera at the device, you’ll see all the details your eyes miss.

Pictured: Phonotrope — the modern take on the Zoetrope

Pictured: an optical illusion

The gimmick behind modern 3D films’ illusion of depth was first discovered in the 19th century. You can look through our vintage stereoscope to see the effect for yourself. Next to the old stereoscope is a glasses-free 3D screen — the latest in 3D technology.

Pictured: a stereoscope from 1901

Next up is our collection of photoelastic objects. They look transparent to the naked eye, but start bursting with colour when looked through a special filter.

Photoelasticity manifests itself when you stress a substance so much, it starts refracting light twice. Apart from being a cool party trick, it is a useful indicator when stress-testing bridges or implants.

Pictured below — another seemingly white screen. If looked at through a special filter, you can see the picture of a colourful dragon.

ITMO University staff often works alongside artists to create artwork for the museum. For example, the “Wave” LED installation was created in collaboration with the Sonicology project, headed by the media artist and composer Taras Mashtalir.

The “Wave” is a two-meter-long sculpture fitted with technology that registers the visitors’ movements and generates audio-visual responses.

Pictured: the “Wave” LED installation

The next room houses the museum’s collection of mirror-based optical illusions. Some of these objects take advantage of anamorphosis to “flatten” images with skewed perspectives.

The next room showcases the museum’s collection of plasma lamps. The visitors are free to touch them.

To the right of the wall of lamps is a special light-absorbing surface. You can draw on it with a flashlight. It faces a light-reflecting surface on the other side of the room. If you were to take its picture with a flash, the end result would be dark and poorly lit — the opposite of the desired effect.

The penultimate room of the museum is dark and filled with luminescent objects, like the glowing map of Russia.

Pictured: a luminescent map of Russia

The last exhibit is called “The Magic Forest”. It is an art object made of mirrors and luminescent threads.

Pictured: the “Magic Forest”

To infinity and beyond

Every day our staff is working on new exhibits and improving the existing ones. A new guided tour starts every 20 minutes. We host a special series of workshops for schoolkids that explains high school optics.

In the near future we’ll be increasing the number of interactive exhibits, talks and workshops. There’s going to be a VR zone with virtual exhibits from the university’s Video 360 Project, as well as artists from around the world. We hope our museum will continue to inspire curiosity in its visitors.

Further reading:

- Lab tour: Functional Materials and Devices of Optoelectronics at ITMO University

- Juggling work and study at the Department of Photonics and Optical Information Technology

- Post-cyberpunk: what you need to know about the latest trends in speculative fiction

- Weekend Picks: light reading for STEM majors