Recently I wrote an article What is Reactive Programming? iOS Edition where in a simple way I described how to build your own Reactive Framework, and helped you to understand that no-one should be scared by the reactive approach. The previous article could now be named How to cook reactive programming. Part 0., since this is a continuation. I would recommend reading the previous article if you are not familiar with the reactive programming concepts.

This article can be read not just by iOS developers. I used only the basic concepts of Swift. You will understand it if you have knowledge of any modern programming language.

Today we are going to talk more about the practical aspects of reactive programming. I've already mentioned it's too easy to make a lot of errors with this approach after you’ve begun using any reactive framework, so I want to show you how to avoid any problems.

The problems

To start, I want to describe some common problems with reactive programming and with the most common approaches nowadays.

Let's begin with reactive problems. The most common fear about reactive programming is that when you start to use it, you can reach a point where there are hundreds of uncontrolled data sequences in your code base and you as a developer no longer have any power over it.

Unpredicted mutations

The first and the biggest problem of what a reactive way could do for you is unpredicted mutations. Let me make an example:

class Foo {

var val: Int?

init(val: Int?) {

self.val = val

}

}

var array: [Foo] = [Foo(val: 1), Foo(val: 2), Foo(val: 3)]

array = array.map { element in

array[0].val = element.val

return element

}

// array == 3, 2, 3For the simplest of reasons, I've replaced the reactive sequence with an array. The example itself is an oversimplified way of how you can make a mistake, doing any reactive things. Nobody can predict where and when you changed data, we have so many ways to do it and there are so many of them hidden under reactive framework implementations.

However, how can we handle this, how can we protect ourselves? First of all, we should move from reference types to the value ones.

struct Foo {

var val: Int?

}

var array: [Foo] = [Foo(val: 1), Foo(val: 2), Foo(val: 3)]

array = array.map { element in

array[0].val = element.val

return element

}

// array == 1, 2, 3Just with this simple change, I protect my array from an unpredicted mutation. As far as you know structs are value types, and they copy themselves all the time (there's a copy on write mechanism, but you’ve got the idea).

However, let’s wait for a moment, and let's try to move one step forward and try to make one radical movement. Let's make variable val a constant.

struct Foo {

let val: Int?

}

var array: [Foo] = [Foo(val: 1), Foo(val: 2), Foo(val: 3)]

array = array.map { element in

array[0].val = element.val // Cannot assign to property: 'val' is a 'let' constant

return element

}Yes! That's the protection I'm talking about. Now we don't have any chance to mutate our data on the way through the data Sequence.

What are we going to do with all this? A mobile application is not a painting, it is not static, we need to mutate data to react on user behavior or any other external changes such as network data or timers. An app is a living thing. So we have two problems to solve. We need to keep our value entities in the floating sequences, and we need somehow to mutate data to show changes to the user. That sounds like a challenge but wait for it, let's talk a little bit about modern architectures. This is an article about architecture after all.

MV family

The problem above is not only about the reactive approach. You can face it everywhere, no matter the paradigm you use. Let's take a small step back and talk a little bit about modern app architectures.

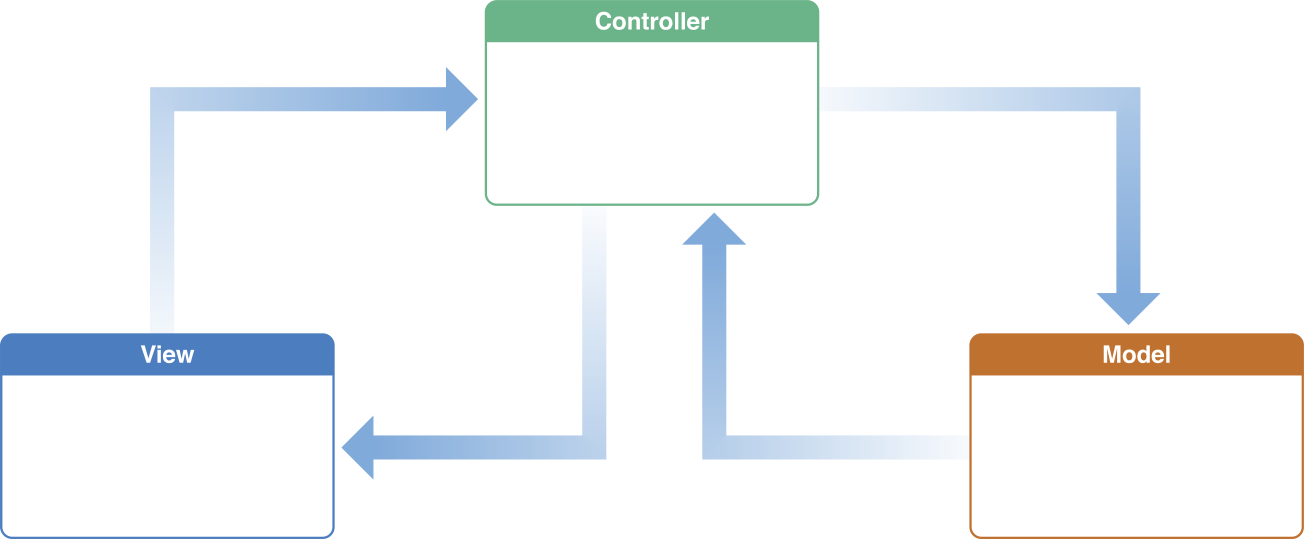

I can bet you’ve seen this guy before. Actually, in my personal opinion, most modern architectures look like this. They could be called the MVsomething family. MVP, VIPER, MVVM, the same but different. I don't want to go deep inside to try to understand what all the differences are between them, you already know this. Let's talk about common things. They are all small pieces, separated by screens, single views, or just a piece of business logic. Whoever is familiar with the topic will understand in advance what I'm getting at. With all these architectures it’s easy to bump into an inconsistent state of the app. Let me provide an example — imagine you have a home page in your app, and this home page depends on the logged-in user. You have a quite complicated app already with a possibility to sign in or sign out the user from different parts of the app. Already understand what I'm talking about? Imagine you decided to sign out from one part of the app and your home page should react on this change. Let me just show a gif as an example.

You can use some sort of user service, which will notify all subscribers to this service about any changes to a user. This approach has two problems. First problem: I think that services should be stateless; they shouldn't hold any information, just perform actions. Second problem: imagine that we have more than one situation where we need to share information between several modules. In this case, we'd have a bunch of dirty services and we'd simply return to the starting point with a lot of floating mutations.

What to do in this situation? I'll give you an answer shortly.

One ring to rule them all

As I said above, an application is a living, changing system. For now, we have two problems, which should be solved. The first problem is that we need to keep data in the sequences immutable. The second one is that we need to stop producing sources of truth inside the codebase. How can we achieve this? What if I say, we can have a single source of truth for the entire application? It sounds ridiculous, but let's try to build this kind of system.

As I said before only one state object is needed. Let's create it.

struct State {

var value: Int?

}Quite easy, yes? The system should be as simple as possible. There is only one source of truth, and every other participant in the codebase observes all changes within this source. Let's try to implement this as well.

protocol Observer {

func stateWasChanged(with newState: State)

}

struct State {

var value: Int?

}

class Store {

var state: State = State() {

didSet {

observers.forEach { observer in

observer.stateWasChanged(with: state)

}

}

}

var observers: [Observer] = []

}

struct Foo: Observer {

func stateWasChanged(with newState: State) {

print("It's newState from Foo: ", newState.value)

}

}

struct Boo: Observer {

func stateWasChanged(with newState: State) {

print("It's newState from Boo: ", newState.value)

}

}

let foo = Foo()

let boo = Boo()

let store = Store()

store.observers = [foo, boo]

store.state.value = 10

// It's newState from Foo: 10

// It's newState from Boo: 10What have I done? There's a state object which holds data from the whole application. Store is an entity, which holds everything. Two Observer objects, which subscribed on every state change. And mostly that's it. By the way, do you remember the user example before? The listed solution perfectly handles this situation. However, there's one big problem. The state was changed directly via store.state.value = 10. This approach could lead to the same problems, which I'm trying to remove right now. I'm going to fix it with a solid сoncept of Event.

One remark. I know that observers are held with a strong reference in Store, and it should be avoided in the real project. You can find out how to achieve this in the previous article. Here I want to save some time. Back to the Event.

enum Event {

case changeValue(newValue: Int?)

}

class Store {

private var state: State

func accept(event: Event) {

switch event {

case .changeValue(let newValue):

state.value = newValue

}

}

}For now, no-one can mutate the state in an unpredictable way. The way of mutation is clear, structured and encapsulated under the Event concept. If you have noticed, for now, you cannot reach State just like a property of the store. I’ve done this on purpose, because reactive programming is about reaction on system changes, not taking data whenever you want, as I described in my previous article.

Wait one moment… Take a look at this signature of standard reduce function in Swift:

func reduce<Result>(_ initialResult: Result, _ nextPartialResult: (Result, Element) -> Result) -> Result

It looks almost the same as our accept function. There's an intialResult as the previous State, and some function to mutate State according to the Event. Let's refactor existing code a little bit.

class Store {

func accept(event: Event) {

state = reduce(state: state, event: event)

}

func reduce(state: State, event: Event) -> State {

var state = state

switch event {

case .changeValue(let newValue):

state.value = newValue

}

return state

}

}That’s much better. However, take a look at this reduce function… It looks like it's completely independent of the Store and mostly any other objects. Why is this so? A reduce function is a pure function — it has its input parameters and one output. It also means that no matter what is going on in Store itself, reduce will work in the same way. So, maybe we should extract it from the store and make it a high order function? It sounds like a great idea, doesn't it? Again, let’s wait one moment. Seems like reduce is closer to State than to Store, so let’s put it under the State namespace.

Here's the final solution for our DIY architecture.

protocol Observer {

func stateWasChanged(with newState: State)

}

struct State {

var value: Int?

static func reduce(state: State, event: Event) -> State {

var state = state

switch event {

case .changeValue(let newValue):

state.value = newValue

}

return state

}

}

enum Event {

case changeValue(newValue: Int?)

}

class Store {

var state: State = State() {

didSet {

observers.forEach { observer in

observer.stateWasChanged(with: state)

}

}

}

var observers: [Observer] = []

func accept(event: Event) {

state = State.reduce(state: state, event: event)

}

}As a result, we've got a simple unidirectional architecture. However, there are so many questions remaining. We don’t live in the synchronous world, where it's possible to put every mutation through the reduce function synchronously. Indeed internet requests or timers couldn’t be added like this to the approach that I’ve introduced before. To resolve this problem, we'll use the SideEffects approach, but I'll write about that in my next article. And I almost forgot about one important thing. Why is the architecture called unidirectional? To provide a clear explanation, I’ll need to make you familiar with the SideEffects as well. So, stay tuned!

PS: This is already the second article about reactive programming, and I haven’t used any framework such as RxSwift or Combine… It actually means that most of you have already been using reactive approaches, without even noticing it. If you don't want to lose any new articles subscribe to my twitter account))

Twitter(.atimca)

.subscribe(onNext: { newArcticle in

you.read(newArticle)

})