Before we start, I'd like to get on the same page with you. So, could you please answer? How much time will it take to:

- Create a new environment for testing?

- Update java & OS in the docker image?

- Grant access to servers?

It will take longer than you expect. I will explain why.

Let's imagine that you expect that an environment will be ready in 2 days after you created a Jira ticket. Just after that, you receive an email that it will be ready in 2 weeks. It's sad but true. But usually, I'm this person from the infrastructure team. I collapse your expectation. Please don't blame on me. I'm not a stiff, opinionated or arrogant person. There are some serious reasons for that. Let me clarify and put things in order.

Infrastructure in the real world

Coincidence + Agreements + Workflow = Infrastructure

Before we start, I would like to clarify what is an infrastructure?. First of all, we should realize how it appears. From my point of view, those processes are pretty similar to each other. So, let's take a look onto the infrastructure for out of the box software for the immense enterprise.

- Coincidence There was an application. The application did not appear from anywhere. It was developed by particular people. Those people had to deploy or run the application somewhere. In our case, somebody sent an email about 10-15 years ago. It was a request to mount servers into racks. It was the beginning of fragile agreements. In your case, it might be a request via telegram, WhatsApp or a phone call. The key thing is that somebody makes an unpredicted request to do something.

- Agreements Time was ticking, thick stream of requests via Jira, emails became waterflow of chaotic requests to create clients like environments. But sometimes you can hear something like: if you want to install server faster, please write on Monday because we visit the server room on Tuesday only. In other words, people try to optimize the process somehow. Agreements are appearing.

- Workflow As a result, you have a formalized process. If you want to have a new environment: please create a task in Jira, fill the form and wait for 7 days, the next available infrastructure engineer will create your environment.

Infrastructure tends to chaos

As we know from our experience, on the one hand, if you want to mount servers to racks, you should know that it is not a rapid process. But on the other hand, a development process must run at full speed.

The world was changing. Our application was containerized. Developers were able to create CoreOS based VMs dynamically. There were docker-compose files for each VM for emulating customers like environments. It was kind of k8s with minimal sets of features. It was before k8s was released. The first answered question was faced. There was a bunch of orphaned YML files in a git repository. There was no responsible person for them. Technical debt was increasing because of fast solutions & kludges. Team members were also changing. The apocalypse came: nobody knew how infrastructure work, nobody saw the whole picture.

Things like that happen. It is not bad or good. There is a heat death of the Universe, that's a given. There is exactly the same thing: infrastructure tends to chaos.

How to deal with chaos?

Formal authorizations & blueprints save from chaos

Createion of an instruction or a blueprint might be the first idea if you want to deal with chaos. There is a short story.

Ages ago, I work in an immense company. The company related somehow to the petrochemical industry. There were a lot of red tapes & formalism inside the company. Once upon a time, someone had to migrate a service and agreed to implement a temporary network scheme for a couple of weeks. The service was shared to the Internet & it was authorized. I was reverse-engineering the petroleum-storage depot in a big airport and found that service. The funny thing was that I found that temp scheme 5 years later. It was an awkward situation because there was direct unrestricted access to a DC core network.

As you can see, sometimes formal authorizations & blueprints can't save from chaos.

Agreements as Code

There is approximately the same situation with Jira tickets. Let's image somebody asks you to prepare a new test environment. On the one hand, you prepare the environment & immediately forget how it has been configured. But on the other hand, if you formalize/automate your agreements as code (it might be custom DSL, Ansible playbook, etc) you have a reproducible solution & the single source of truth. It sounds great: somebody commits to git changes & it automatically appears in the production infrastructure. But you may ask, does it worth the effort?

Think twice before you code your agreements

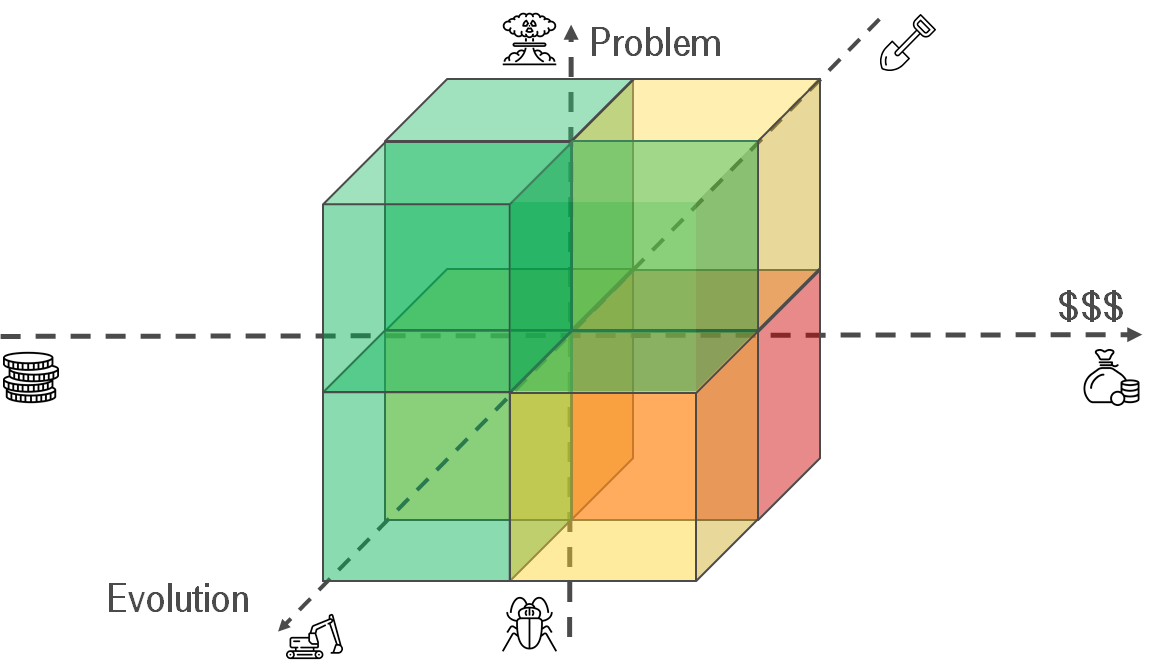

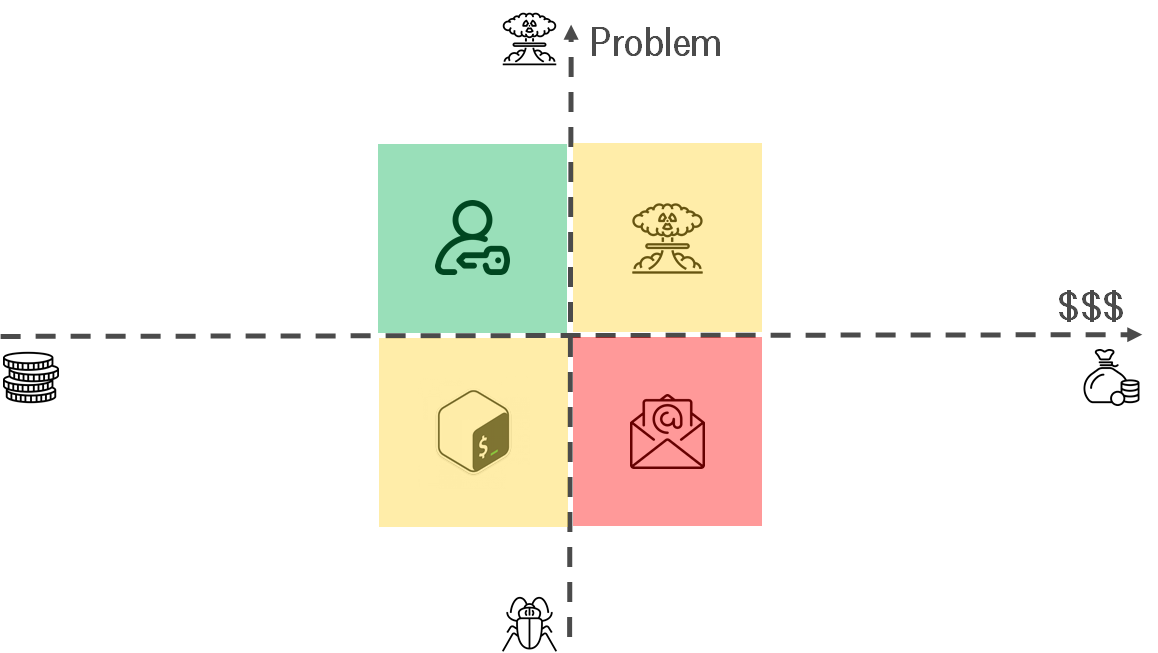

Does it make sense to automate agreements? I use the decision-making matrix for answering the question. Conceptually it looks like the Eisenhower box.

- Problem — How big is your problem? Is it discomfort or apocalypse?

- $$$ — How much does it cost to deal with the problem?

Let me share some examples:

- Big problem, small price — do it. Usually, you can easily replace instruction "how to grant permissions to a user" via script. It formalizes your agreements.

- Small problem, small price — think. If you have free time, it makes sense. On the one hand, it might be worthless to get knowledge about rare unique REST API service if you want to update DNS annually. But on the other hand, it might be a long-term investment & make sense.

- Small problem, big price — ignore. How often should you email footer? Annually? One time per 3 years?

- Big problem, big price — think twice. If you don't have enough experience, you might make a situation worse. Let's imagine that scripts for automating your routine have become standard in the company. Everyone uses it. Nobody knows how it works. You face the apocalypse. It's time for the IaC refactoring.

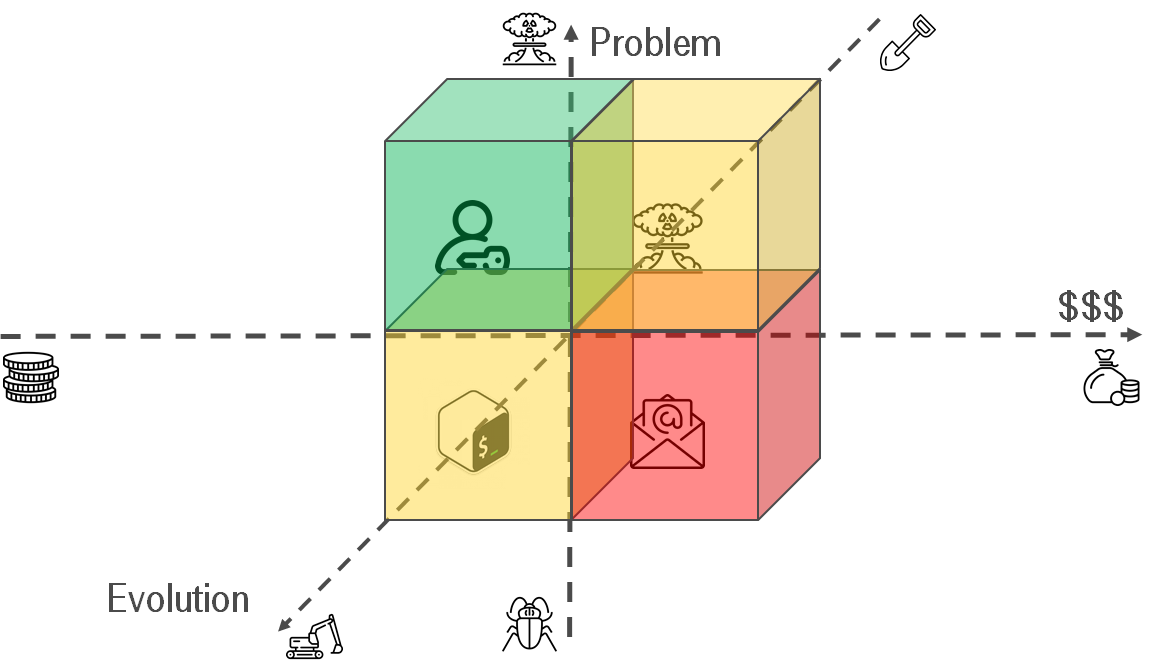

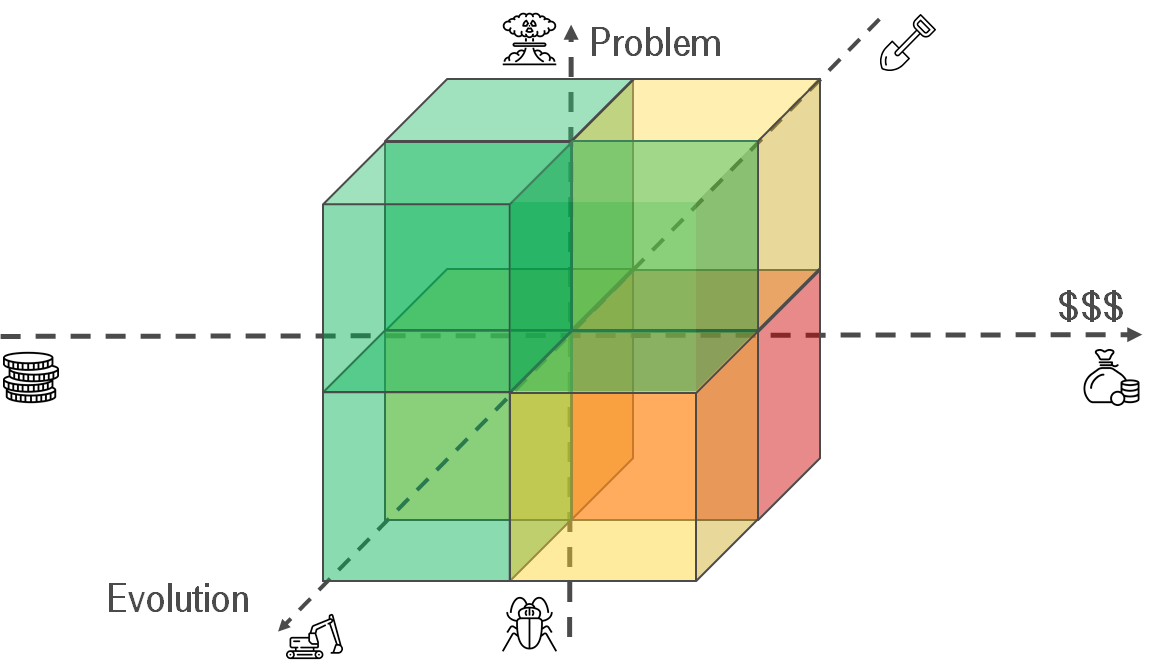

Manual work -> Mechanization -> Automation

Let's try to look from a different perspective. Your processes might be automated on a different level.

- Manual work — there is no automation at all. You are doing everything by hands, collecting cutting edges & corner cases. As a result, you will know the whole process from A to Z.

- Mechanization — It's first shot to simplify routing. It might be an article in confluence. Later this article will help to create a script and code your agreements.

- Automation — People maintain processes as minimum as possible. There are some * as Service. It allows other teams to automate their processes.

To evolute, or not to evolute: that is the question.

- Serious problem, trivial automation — do it. Instead of the script for granting permissions, you can configure an LDAP integration. Instruction -> Script -> LDAP.

- Trivial problem, trivial automation — make sense. In the long term, it makes sense. Maybe, you will reuse your scripts somehow. The key thing is that your knowledge is stored and you should not reinvent the wheel. This foundation can be used for creating * as Service in future. i.e. I have private GitHub repo and store my scripts there.

- Trivial problem, serious automation — think. For someone, it might be important to easily update email footer. i.e. There is a project for generating legal footers for emails & integrating it with the MS exchange. Also, I've heard about the immense outsource company. The company has a web portal. Each employee can get his email footer.

- Serious problem, serious automation — make sense. If our agreements are presented as code then you will be able to refactor it in case of the apocalypse.

It's a part of the infrastructure nature that agreements are formalizing as code and tending to be * as Service.

Infrastructure can be refactored, but think twice before that

Sooner or later, your infrastructure increases the number of agreements. It's tending to chaos. You can face the agreements drift between your ideal model of infrastructure and real picture of the world. As a result, you might want to put things in order. There are some possible reasons for that:

- Get knowledge about how it works under the hood.

- Increase the velocity of applying changes.

- Decrease the number of downtimes.

- ...

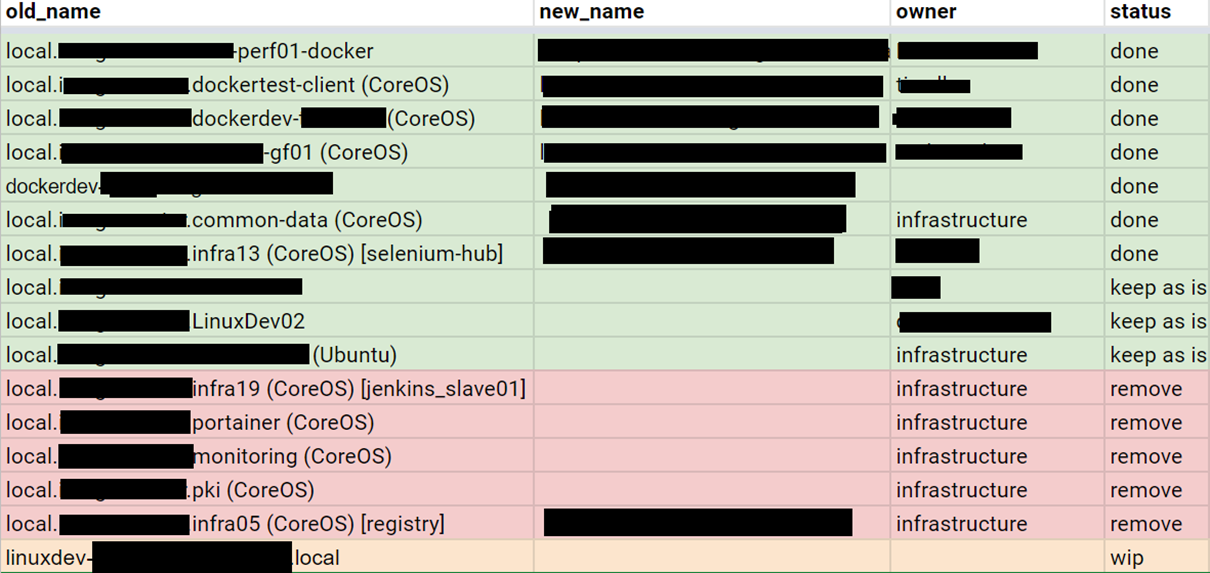

Ansible: CoreOS to CentOS, 18 months long journey

There was a custom configuration management solution. It looked like IaC. It behaved like IaC. But it was hard to maintain this solution. The reason for that was that it was too fragile & nobody wanted to support it. As a result, it was changed. However, it took 18 months.

You can ask me: 'Why so long?'. There are some answers in the article Ansible: CoreOS to CentOS, 18 months long journey. In general, the answer is because changing processes, agreements and workflows. Migration is prune determined process & It follows the Pareto principle:

- 80% of the time was spent on preparation & 20% on migration.

- 80% VMs configuration rewriting took 20% of our time.

From the top-level perspective, it is as easy as pie:

- Create a list of servers.

- Select the first one.

- Determine & fix agreements somehow.

- Realize how it works.

- Code it.

- GOTO 2.

How to test Ansible and don't go nuts

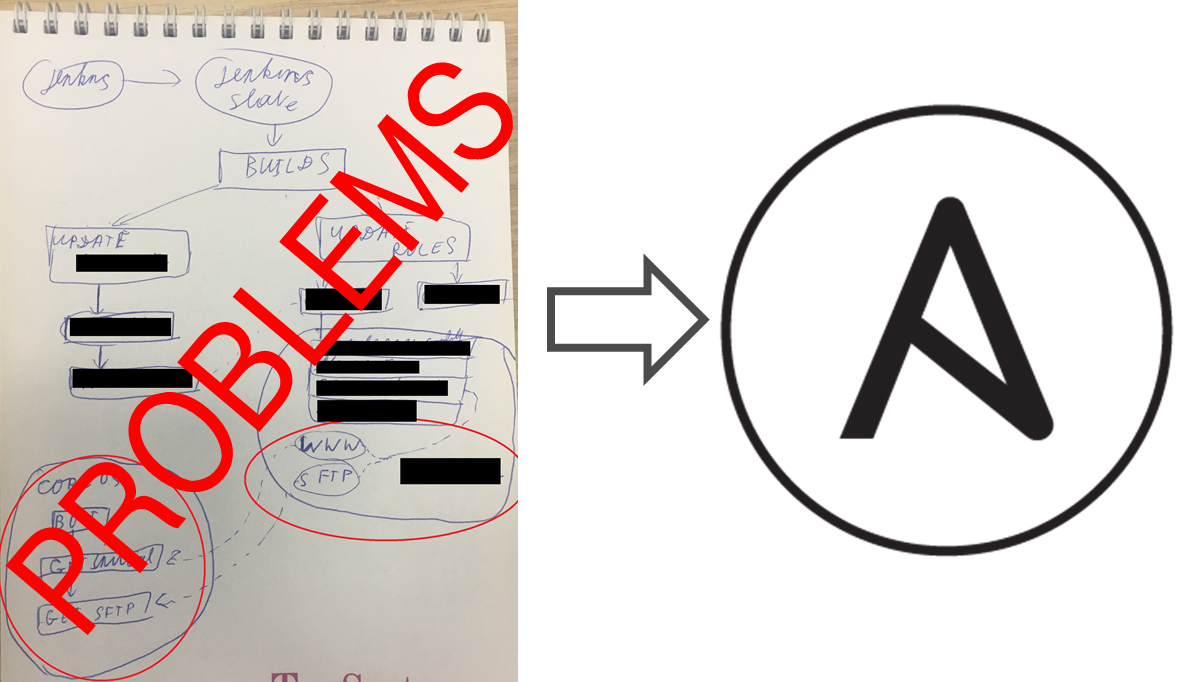

There was a project. It was a casual project, nothing special. There were operations engineers and developers. They were dealing with exactly the same task: how to provision an application. However, there was a problem: each team tried to do it uniquely. They had decided to deal with it & use Ansible as the source of truth. Sooner or later, they realized that the playbooks were not stable. They were occasionally crashing. As a result, there was a task to stabilize it.

You can read the whole story in the article How to test Ansible and don't go nuts. To make a long story short:

- Create a list of existing roles.

- Get the first one.

- Cover by tests & formalize agreements.

- Modify, fix bugs.

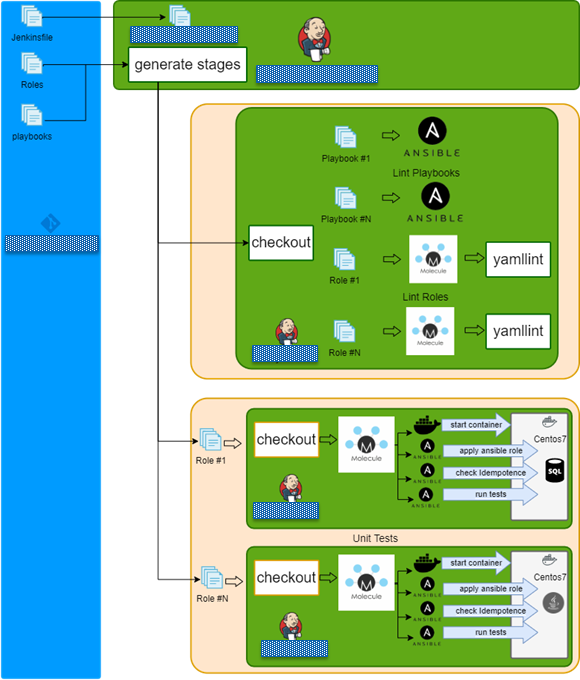

How does the testing process work under the hood?

For historical reasons, there was a monolith repository with all Ansible roles. The Jenkins multi-branch pipeline was created.

The pipeline top-level overview is:

- Checkout repo.

- Read configs.

- Generate dynamic build stages.

- Run lint playbook stages in parallel.

- Run lint role stages in parallel.

- Run syntax check role stages in parallel.

- Run test role stages in parallel.

- Finish.

IaC refactoring

It's totally ok that infrastructure is changing and evolving into a huge pile of scripts or bunch of * as Service. It is a pretty good thing because you can refactor it. I guess you've noticed there is something common in these cases:

- Measure.

- Check that you have enough knowledge & time.

- Select small piece of infrastructure.

- Understand how it works.

- Formalize agreements

- Cover IaC by tests.

- Take a rest.

- Repeat...

It is not really important how to shave the yak. It might be stickers on a wardrobe, tasks in Jira or a spreadsheet in google docs. The main idea is to track current status & understand how it is going. By its nature, this process is similar to code refactoring but with some limitations on tooling. You should not burn out during refactoring, because it is a long boring journey. Also, I'd like to emphasize that you should have:

- Reason — You should understand the reason & desired target. It helps you to understand then that time to stop has come.

- Time — It should be a part of a daily routine. It should be planned in your schedule. Without that, you try to get rid of refactoring burthen in the middle of the journey.

- Knowledge — Insane changes can increase entropy in your system. It can push you closer to chaos & apocalypse.

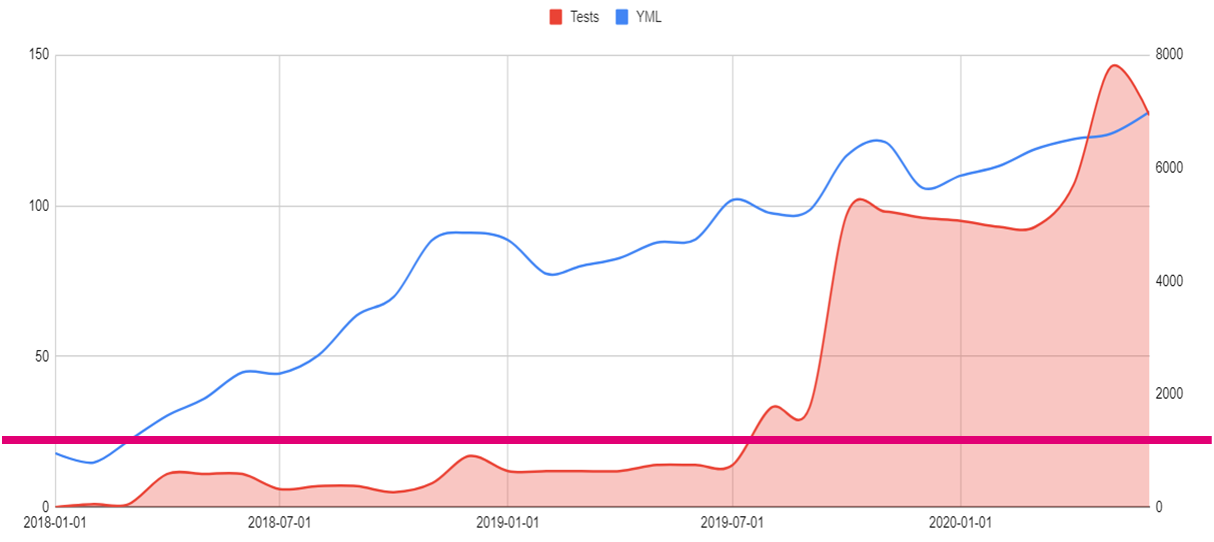

Accelerating acceleration

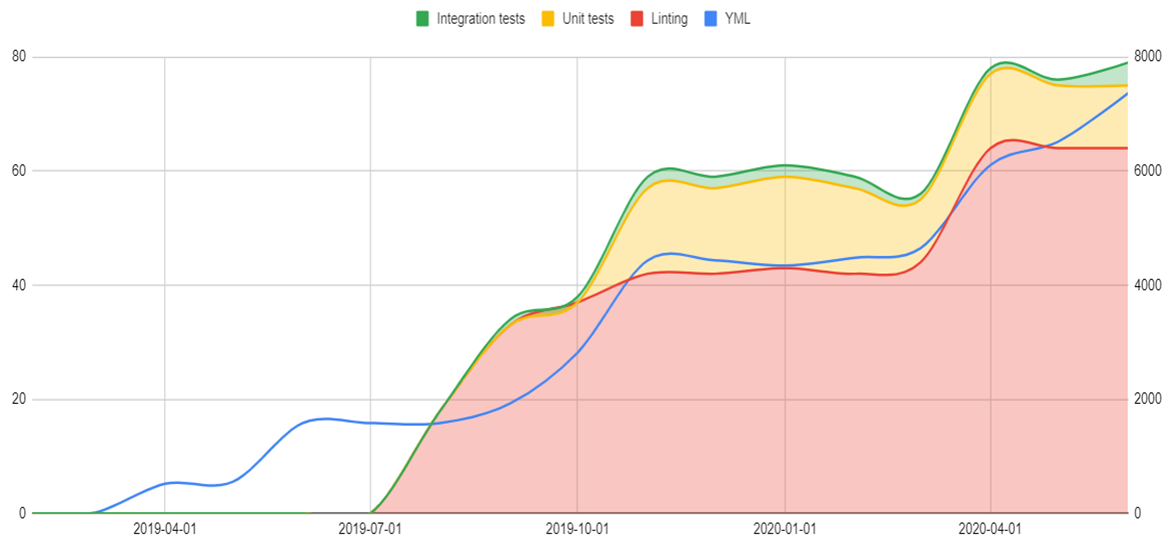

- Horizontal axis — timeline.

- Right vertical axis — SLOC for Ansible roles(blue line).

- Left vertical axis — the number of tested/linted roles/playbooks.

- Blue line — Source Lines Of Code in YAML files.

- Red filler — the number of tested roles/playbooks.

- Magenta line — the number of engineers.

After some time, the velocity of changing infrastructure might go down. It is totally ok. From my point of view, there is a correlation between the number of agreements & SLOC of your IaC. I'm not 100% sure that it's the best way to visualize agreements, but it looks like there are some remarks:

- The amount of code is constantly growing.

- The amount of tests is exponentially growing.

- The amount of tests correlates with the amount of code with a time gap.

- The number of engineers is constant.

There is a conclusion from that. We can support IaC growth with a constant amount of engineers because of IaC tests. In other words, IaC testing increases the velocity of changes and makes it cheaper.

Use IaC testing pyramid. Don't wait!

In 2019 I made the speech Lessons learned from testing Over 200,000 lines of Infrastructure Code. It was about the similarity between IaC and code development. Especially, I was talking about the IaC testing pyramid. You can create the whole infrastructure from scratch for each commit, but, usually, there are some obstacles: The price is stratospheric & it requires a lot of time. It makes to re-use testing pyramid from the software development world:

- Static Analysis — a lot of simple, rapid, primitive tests in your foundation. Linters like shellchek, ansible lint, yamllint.

- Unit — you run something to validate your code molecule / kitchen + testinfra / inspec. So, your IaC should be constructed from simple bricks: roles, modules.

- Integration — They look like unit tests, but they are testing not small block, but the whole server configuration.

- E2E — check that group of servers work correctly as an infrastructure.

When should I start testing my IaC?

It's a pretty good question. Let me share some stories.

Project №1

- Horizontal axis — timeline.

- Right vertical axis — SLOC for Ansible roles(blue line).

- Left vertical axis — the amount of tested/linted roles/playbooks. It's used for the stacked area(integration tests, unit tests, linting).

- Blue line — Source Lines Of Code in YAML files.

- Stacked area — the number of tested roles/playbooks.

We started from integration tests. It was hard to maintain & it was working to slow for developing IaC. As a result, we decided to rebuild the process from scratch. We started from linting. After that, our process evoluted to unit tests.

Project №2

There was another project. We started from linting from the very beginning with a small codebase. It grew smoothly & painless.

The lesson learned:

- Tests are changed through the time.

- For different project stages, it's possible to use different approaches.

- Testing is a long term journey.

Let me share my estimations about numbers of SLOC:

- 2000 — linting must be started from the very beginning.

- 4000 — unit tests should be written. You you don't run the molecule at this stage you will have problems in the future.

- 6000 — integration tests can be implemented.

- 8000 — E2E tests might be presented.

Lessons learned

- Infrastructure tends to chaos.

- Think before you code your agreements.

- Manual work -> Mechanization -> Automation.

- Infrastructure can be refactored, but think twice before that.

- IaC simplifies refactoring & increases the velocity of changes.

- Use IaC testing pyramid. Don't wait!

Links

It is text version of my speech at TechLeadConf 2020-06-09 (RU).

- Slides (RU)

- Video (RU)

- A list of awesome IaC testing articles, speeches & links

- Lessons learned from testing Over 200,000 lines of Infrastructure Code

- How to test Ansible and don't go nuts

- Ansible: CoreOS to CentOS, 18 months long journey

- Podcast nsfw.co.in/04 Agreements as Code (RU)

- Russian Version

- Cross post from personal blog