The thoughts I’m going to relate in this post may seem obvious and even trivial to some of you, but my experience with water cooler chats with my workmates shows that many people, including tech-savvy ones, let alone tech laymen, did not give this problem any consideration.

When we start discussing the issue of never using public WiFi on transport, in cafes, hotels, etc, the first major problem that is usually pointed out is either the complete lack of encryption or the usage of the same encryption key for all users. Many will justly return that virtually all websites and services are now using HTTPS, so your passwords and personal data cannot be intercepted by an attacker listening to the traffic.

Those who are proficient in technology or soundly paranoid use encrypted VPNs when working on public networks, thus mounting an additional layer of defence.

However, I’d like to talk about something else.

In accordance with the current law of some countries (e.g. the Russian Federation; many other countries have similar laws), the key prerequisite of access to a free WiFi connection is user authentication. Users who want to connect to a public network must undergo personal authentication and the identification of their devices.

When you connect to a free WiFi for the first time, you automatically get redirected to an authentication page which, for example, may look like this:

The authentication requires one or multiple steps:

Almost every time you go through authentication, the service provider notes down the MAC address of your device plus a certain token that explicitly identifies you (your phone number, username for your State Services account, agreement number, etc.). This is done to spare you the need to do it all over again when you connect to the same network next time — the service provider’s router will recognize your phone, tablet or laptop by their MAC address and automatically apply the appropriate access rights. In most cases, your MAC address is the only way for the provider to identify you as a user.

Now let’s imagine a more than a realistic situation.

You, being a law-abiding citizen, come to a public place, such as a cafe or a subway car, authenticate using your phone number or in any other available way, use the Web and then disconnect from the network and leave the place.

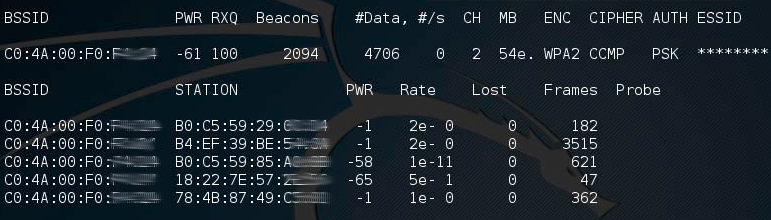

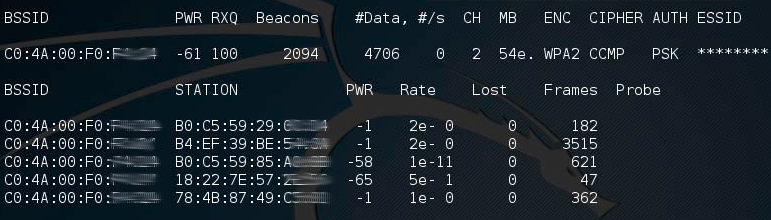

Just as you are there, another, not quite law-abiding citizen, happens to be nearby with an ordinary looking laptop equipped with a standard WiFi adapter working in the monitor mode and a set of utilities from the aircrack-ng suite. Using all that equipment, the bad guy is quietly listening in, registering the MAC addresses of any devices that connect to the network, exchange traffic with the hotspot and then disconnect from it. Here is how it may look:

After you have left the area covered by the WiFi network, the bad guy changes the MAC address of his WiFi adapter to the MAC address of your device, connects to the network, gets recognized as an existing user (i.e. you) and receives access to the Internet without any authentication.

Mind you, the above scheme does not necessarily carries in it malicious intentions. Some people (all characters and events are fictitious, any resemblance is accidental) do this to use a subway WiFi network in an ad-free mode (by finding a MAC address of a person who paid for a premium account with advertisement removed).

Having successfully logged in to the network, the bad guy can do something that does not agree with the current legislation, such as write a post on social media with racist insults and appeals, hack some web servers or make financial fraud, distribute pirated software or child pornography, report about terrorist attack planning, and so on.

Once the investigation officers send an inquiry to the service provider whose network was used to make the offense, rather than pointing to the bad guy, the logs will point to you as the legal owner of the device with the MAC address recorded in the access log.

Ideally, this scenario will fall apart before the investigation even starts.

In a less ideal, but still optimistic case, you will have to spend time and effort to prove your innocence, e.g. enrol experts who will provide evidence that a MAC address cannot be seen as a unique identifier of a particular device and a particular user, gather witnesses’ testimonials and CCTV footage (if it is not deleted due to the time passed) proving that you had already left the place when this happened, and pray that the judge does not reject your plea for attaching this evidence to your case due to its “irrelevance.” (yep, this sometimes happens in Russia).

Case studies are well known, such as the case against Dmitry Bogatov, a Tor node operator whose IP address was used by an unknown person to call for civil disorder. Despite the CCTV footage explicitly proving that at the time the offense was committed, Dmitry had been at a fitness club, not at home with his laptop; despite the findings of experts who said that an IP address could not be directly linked to someone’s identity, Bogatov was arrested and later put into home detention, with his criminal case closed only a year later. Had this case not received a broad media coverage or had Dmitry not been supported by human rights organizations all over the world, this could all have ended up much nastier than it had.

In a worst-case scenario… well, let’s not mention such scenarios, as you will imagine the picture on your own.

How can you prevent this from happening? Sadly, you can’t. The stumbling blocks are the unreliability of the very authorization and authentication methods used by network carriers and the specifics of our law-enforcement and judicial systems. At the moment, I can’t think of any technically feasible ways to avoid such situations for ordinary users (I don't consider the option where you use SIM cards purchased in a third party’s name for reasons mentioned above). There is only one logical suggestion here: do not use public WiFi networks.

Bear in mind that vigilance is good not only for using public WiFi. The WiFi routers of the overwhelming majority of home users today use the WPA2-PSK encryption protocol, which is also exposed to the risk of brute-forcing the encryption key, which, in case of using simple passwords (and as computing speed keeps growing, this will also concern more sophisticated passwords), conceals the threat of intruders potentially connecting to a home WiFi network and going online on behalf of the router owner. This problem can be solved using technology (for example, you can configure the equipment so that anyone connecting to a WiFi network will only get access to a VPN which then serves as a gateway to the outer online world, or you can use WPA-802.1X, but in both cases you would need to implement them in hardware), however very few ordinary users will, unfortunately, go to all this trouble.

When we start discussing the issue of never using public WiFi on transport, in cafes, hotels, etc, the first major problem that is usually pointed out is either the complete lack of encryption or the usage of the same encryption key for all users. Many will justly return that virtually all websites and services are now using HTTPS, so your passwords and personal data cannot be intercepted by an attacker listening to the traffic.

Those who are proficient in technology or soundly paranoid use encrypted VPNs when working on public networks, thus mounting an additional layer of defence.

However, I’d like to talk about something else.

In accordance with the current law of some countries (e.g. the Russian Federation; many other countries have similar laws), the key prerequisite of access to a free WiFi connection is user authentication. Users who want to connect to a public network must undergo personal authentication and the identification of their devices.

When you connect to a free WiFi for the first time, you automatically get redirected to an authentication page which, for example, may look like this:

The authentication requires one or multiple steps:

- Entering your cell phone number and receiving a text with a code or a call to your phone. In line with the approved amendments to the law, SIM cards can only be sold at dedicated points of sale, provided the customer presents the appropriate identity documents. On top of that, the competent authorities are currently planning on tackling “shadow” SIM cards and cards purchased in a third party’s name.

- Authentication via the Unified Identification and Authentication System (Russian: ЕСИА) aka State Services, whereby to create an account there, you also need to produce identity documents.

- Some ISPs allow their clients connect to their own public WiFi networks by entering their username and password they use for home Internet, which, in its turn, is provided based on a contract containing the user’s passport details.

Almost every time you go through authentication, the service provider notes down the MAC address of your device plus a certain token that explicitly identifies you (your phone number, username for your State Services account, agreement number, etc.). This is done to spare you the need to do it all over again when you connect to the same network next time — the service provider’s router will recognize your phone, tablet or laptop by their MAC address and automatically apply the appropriate access rights. In most cases, your MAC address is the only way for the provider to identify you as a user.

Now let’s imagine a more than a realistic situation.

You, being a law-abiding citizen, come to a public place, such as a cafe or a subway car, authenticate using your phone number or in any other available way, use the Web and then disconnect from the network and leave the place.

Just as you are there, another, not quite law-abiding citizen, happens to be nearby with an ordinary looking laptop equipped with a standard WiFi adapter working in the monitor mode and a set of utilities from the aircrack-ng suite. Using all that equipment, the bad guy is quietly listening in, registering the MAC addresses of any devices that connect to the network, exchange traffic with the hotspot and then disconnect from it. Here is how it may look:

After you have left the area covered by the WiFi network, the bad guy changes the MAC address of his WiFi adapter to the MAC address of your device, connects to the network, gets recognized as an existing user (i.e. you) and receives access to the Internet without any authentication.

Mind you, the above scheme does not necessarily carries in it malicious intentions. Some people (all characters and events are fictitious, any resemblance is accidental) do this to use a subway WiFi network in an ad-free mode (by finding a MAC address of a person who paid for a premium account with advertisement removed).

Having successfully logged in to the network, the bad guy can do something that does not agree with the current legislation, such as write a post on social media with racist insults and appeals, hack some web servers or make financial fraud, distribute pirated software or child pornography, report about terrorist attack planning, and so on.

Once the investigation officers send an inquiry to the service provider whose network was used to make the offense, rather than pointing to the bad guy, the logs will point to you as the legal owner of the device with the MAC address recorded in the access log.

Ideally, this scenario will fall apart before the investigation even starts.

In a less ideal, but still optimistic case, you will have to spend time and effort to prove your innocence, e.g. enrol experts who will provide evidence that a MAC address cannot be seen as a unique identifier of a particular device and a particular user, gather witnesses’ testimonials and CCTV footage (if it is not deleted due to the time passed) proving that you had already left the place when this happened, and pray that the judge does not reject your plea for attaching this evidence to your case due to its “irrelevance.” (yep, this sometimes happens in Russia).

Case studies are well known, such as the case against Dmitry Bogatov, a Tor node operator whose IP address was used by an unknown person to call for civil disorder. Despite the CCTV footage explicitly proving that at the time the offense was committed, Dmitry had been at a fitness club, not at home with his laptop; despite the findings of experts who said that an IP address could not be directly linked to someone’s identity, Bogatov was arrested and later put into home detention, with his criminal case closed only a year later. Had this case not received a broad media coverage or had Dmitry not been supported by human rights organizations all over the world, this could all have ended up much nastier than it had.

In a worst-case scenario… well, let’s not mention such scenarios, as you will imagine the picture on your own.

How can you prevent this from happening? Sadly, you can’t. The stumbling blocks are the unreliability of the very authorization and authentication methods used by network carriers and the specifics of our law-enforcement and judicial systems. At the moment, I can’t think of any technically feasible ways to avoid such situations for ordinary users (I don't consider the option where you use SIM cards purchased in a third party’s name for reasons mentioned above). There is only one logical suggestion here: do not use public WiFi networks.

Bear in mind that vigilance is good not only for using public WiFi. The WiFi routers of the overwhelming majority of home users today use the WPA2-PSK encryption protocol, which is also exposed to the risk of brute-forcing the encryption key, which, in case of using simple passwords (and as computing speed keeps growing, this will also concern more sophisticated passwords), conceals the threat of intruders potentially connecting to a home WiFi network and going online on behalf of the router owner. This problem can be solved using technology (for example, you can configure the equipment so that anyone connecting to a WiFi network will only get access to a VPN which then serves as a gateway to the outer online world, or you can use WPA-802.1X, but in both cases you would need to implement them in hardware), however very few ordinary users will, unfortunately, go to all this trouble.