I don't know about you, but I really like to get inside all sorts of systems. In this article, I’m going to tell you about the internals of Lua tables and special considerations for their use. Lua is my primary professional programming language, and if one wants to write good code, one needs at least to peek behind the curtain. If you are curious, follow me.

Lua has several implementations and several versions. In this article, I'm going to discuss mostly LuaJIT 2.1.0, which is used in Tarantool. Our version is a bit patched as compared to the authentic LuaJIT, but the differences don't impact tables.

There is another good presentation about tables in PUC-Rio implementation[1], if you're interested.

Tables in Lua are the only composite data type designed to suit any purpose. A table can be used both as a data array (if the keys are integer-valued) and as a key-value repository. Values of any type can be used as keys (except for nil). Scientifically speaking, a table is an associative array [2].

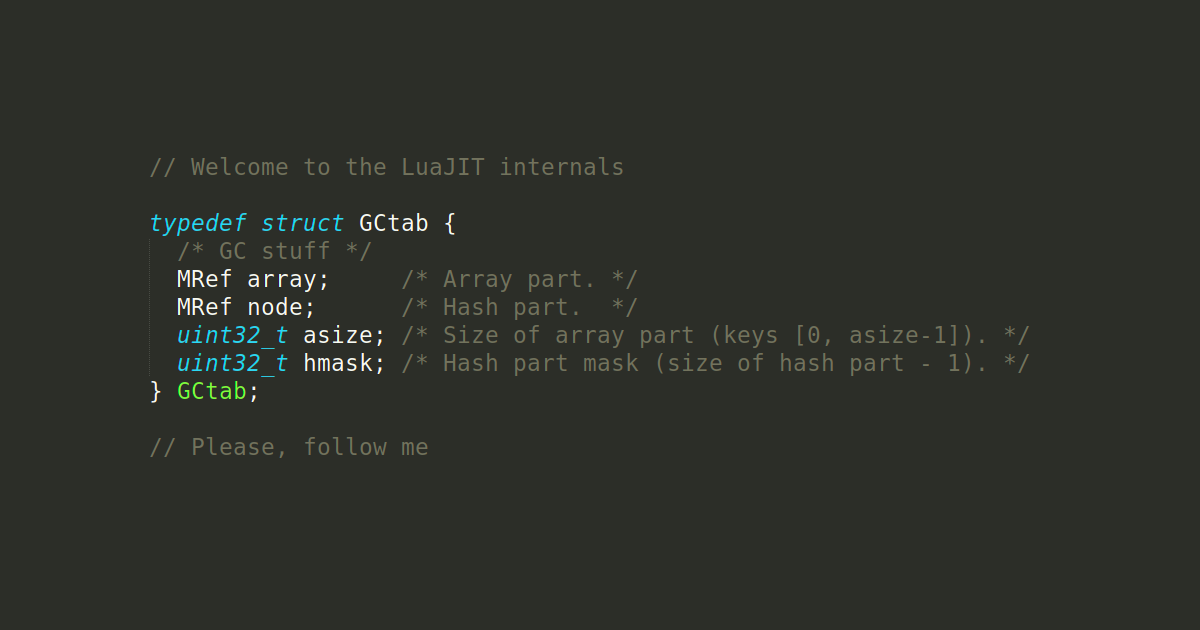

In LuaJIT sources [3], a table is represented by the following structure (I've omitted a part of fields which are not relevant here for simplicity):

A table has two parts: array and hashmap. Both are represented by continuous storage areas. I was about to describe the logic LuaJIT is guided by when new elements are inserted, but this a rather sophisticated algorithm. Moreover, as a Lua developer, I have no need to speculate about what a table looks like on the inside. There's something that is more important: two tables may contain the same keys and values, but differ in terms of internal representation. This internal representation will affect behaviors of some functions, which I'm going to discuss here.

For demonstration, I took LuaJIT source code and patched

The most complete version of code from the publication, including all the experiments, can be found on GitHub [4]. Conceptually, this is what the code looks like:

Let me show how this works:

We've created an empty table, and LuaJIT has allocated storage space for 0 array elements and 1 element in hashmap, whereto it has placed

String keys are added to hashmap as expected. Here the first reason already becomes visible why the internal representation of tables may differ: hash collisions. To resolve hash collisions, LuaJIT uses a hybrid of open addressing and separate chaining methods [5] (thanks to Igor Munkin for clarification).

Depending on the order in which elements are added to the table, their order during integration will differ. For demonstration, I've set up one more auxiliary function

A complete version of the code can still be found on GitHub [4]. For brevity, I'm going to demonstrate here only its operating principle.

One more interesting fact about the internals of tables: deletion of value does not lead to deletion of key. Sounds like Captain Obvious, but it's true.

This is done for a purpose, to make it possible to delete values and not disturb iteration order. What is strongly discouraged is to add new keys to the table within the cycle as reallocation or re-hashing may occur, and then iteration will bust.

Additional note from Igor Munkin: the reason is lookup in general, not iteration. Collisions are resolved by the chain method. Generally, when the main node is deleted for the searched key, the link to the colliding element needs to be reassigned to the predecessor (if present) of this main node. Task O(n) to search for it needs to be performed when deleting. The cost of a search does not worsen when a dead node is present on the way to collision resolution. See also [5].

OK, iteration for string keys is clear, no more questions. Now let's talk about the second half of the table — the array.

Lua is often made fun of because indexation in this language starts with one. Interestingly, LuaJIT allocates space to store the null element anyway. This makes it easier for it to avoid multiple addition / deduction of one.

If it appears to you that arrays don't have any surprises, then I'm here to disappoint you (or make you happy) — they do:

I've changed syntax a bit, so one element gets to the array, and another gets to the hashmap. So consider yourself warned: it's no use taking guesses about internal representation as your guess can turn out to be wrong at any time.

Answer: LuaJIT interpreter, same as regular Lua, generates different bytecode in these two cases.

In the first case, space is allocated to place two array elements, which is logical.

In the second case, 1 element in the array and 1 in the hashmap.

But, still, my primary concern as a developer is the correctness of my code. If LuaJIT is comfortable with presenting tables differently, it has the right to do it this way. For me, the main thing is that it is done seamlessly. So I suggest that we go over functions and spell out the expectations.

Iterator

FAQ: WAT?

Answer: Function

This trick works exclusively due to pre-allocation. Another element being added to the table and the following re-hashing (which is a rather expensive and complex operation) will totally remove the veil of mystery from the table:

By no means do I want to sound paranoid, and I consider this case highly implausible. In 99.9% of instances, «arrays» in Lua will really be represented by arrays, and the iteration order will be sequential.

Much more often, errors do occur because of array length being calculated incorrectly. The main thing one needs to know about it is a definition from Lua specification [6].

That is to say, not every table has the property of length. Surprise — undefined behavior can occur in Lua. Tables with «holes» simply don't have such a property. In LuaJIT implementation, function

LuaJIT searches for a «boundary» in the table. If there are missing values in the array, and thus several boundaries exist, then, depending on the circumstances, LuaJIT will be able to find any of those — and will be right:

FAQ: WAT?

Answer: These two tables differ in terms of internal representation.

LuaJIT searches for a boundary with a binary search, and it first checks the last element in the array. If it exists, search proceeds to the hashmap, otherwise it continues in the array.

And this definitely does not sound paranoid as there have been such errors in the past. Table length is implicitly used in other functions, so undefined behavior is something you don't want to play with. To be fair, it should be noted that in arrays without holes, the behavior is strictly determined and does not depend on internal representation.

Table sorting always works within the range from 1 to

Lua allows length to exist though, even when string keys are present, but as far as we are talking about typical contracts of functions, hybrid tables rarely work.

Where do those arrays with holes really come from? A rare weird case, as it might seem. But nope, there are dangers lurking every step of the way:

Multiple periods here are not an ellipsis but rather a designation of a variable number of function arguments.

Then someone calls this function with arguments

Lua specification [8] reads:

To avoid inadvertent loss of tail, instead of implicit

In LuaJIT (and in Tarantool),

This is where black magic comes into play —

This one is a good operator, predictable enough.

No internal representation differences can affect it, and «holes» don't lead to undefined behavior — iteration simply stops.

An attentive reader could have noticed that I have already used twice a strange expression

This is a notorious pitfall in Tarantool named

Another pitfall in LuaJIT is the use of FFI types as a table key. This issue is not so frequently discussed in Lua manuals because there are no FFI types in vanilla version of Lua. But LuaJIT can surprise you and backfire. Here's what's written in the manual [11]:

Simply put, for

I hope no one in one's right mind would write things like this in code, but

As long as we are on this subject, note that it's possible to obtain unexpected results without using too, though I've never seen this in practice:

[1] The basics and design of Lua table (or the same at slideshare.net).

[2] Programming in Lua — Tables

[3] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT — lj_obj.h

[4] GitHub — rosik/luajit:habr-luajit-tables

[5] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT — Issue #494.

[6] Lua 5.2 Reference manual — The Length Operator

[7] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT lj_tab.c

[8] Lua 5.1 Reference manual — Basic Functions — unpack

[9] Lua 5.1 Reference manual — Basic Functions — select

[10] Lua 5.1 Reference manual — The Stack

[11] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT — ext_ffi_semantics.html

[12] Tarantool » 2.2 » Reference » Built-in modules reference » Module uuid

[Bonus] Learn X in Y Minutes, where X=Lua

Lua has several implementations and several versions. In this article, I'm going to discuss mostly LuaJIT 2.1.0, which is used in Tarantool. Our version is a bit patched as compared to the authentic LuaJIT, but the differences don't impact tables.

There is another good presentation about tables in PUC-Rio implementation[1], if you're interested.

Rundown

Tables in Lua are the only composite data type designed to suit any purpose. A table can be used both as a data array (if the keys are integer-valued) and as a key-value repository. Values of any type can be used as keys (except for nil). Scientifically speaking, a table is an associative array [2].

-- Empty table

local t1 = {}

-- Table as an array

local t2 = { 'Sunday', 'Monday', 'Im tired' }

-- Table as a hashtable

local t3 = {

cat = 'meow',

dog = 'woof',

cow = 'moo',

}

-- Ordered map

local t4 = {

'k1', 'k2', 'k3' -- stored in the array part

['k1'] = 'v1', -- stored in the hash part

['k2'] = 'v2', -- stored in the hash part

['k3'] = 'v3', -- stored in the hash part

}

Anatomy of tables

In LuaJIT sources [3], a table is represented by the following structure (I've omitted a part of fields which are not relevant here for simplicity):

typedef struct GCtab {

/* GC stuff */

MRef array; /* Array part. */

MRef node; /* Hash part. */

uint32_t asize; /* Size of array part (keys [0, asize-1]). */

uint32_t hmask; /* Hash part mask (size of hash part - 1). */

} GCtab;

A table has two parts: array and hashmap. Both are represented by continuous storage areas. I was about to describe the logic LuaJIT is guided by when new elements are inserted, but this a rather sophisticated algorithm. Moreover, as a Lua developer, I have no need to speculate about what a table looks like on the inside. There's something that is more important: two tables may contain the same keys and values, but differ in terms of internal representation. This internal representation will affect behaviors of some functions, which I'm going to discuss here.

For demonstration, I took LuaJIT source code and patched

tostring() method a bit so that it would print out the size and all the contents of C structure in stdout using printf().What the patch is about

The most complete version of code from the publication, including all the experiments, can be found on GitHub [4]. Conceptually, this is what the code looks like:

diff --git a/src/lj_strfmt.c b/src/lj_strfmt.c

index d7893ce..45df53c 100644

--- a/src/lj_strfmt.c

+++ b/src/lj_strfmt.c

@@ -392,6 +392,51 @@ GCstr * LJ_FASTCALL lj_strfmt_obj(lua_State *L, cTValue *o)

if (tvisfunc(o) && isffunc(funcV(o))) {

p = lj_buf_wmem(p, "builtin#", 8);

p = lj_strfmt_wint(p, funcV(o)->c.ffid);

+ } else if (tvistab(o)) {

+ GCtab *t = tabV(o);

+ /* print array part */

+ printf("-- a[%d]: ", asize);

+ for (i = 0; i < asize; i++) {

+ // printf(...);

+ }

+

+ /* print hashmap part */

+ printf("-- h[%d]: ", hmask+1);

+ for (i = 0; i <= hmask; i++) {

+ // printf(...);

+ }

} else {

p = lj_strfmt_wptr(p, lj_obj_ptr(o));

}

Let me show how this works:

t = {}

tostring(t)

-- table: 0x40eae3a8

-- a[0]:

-- h[1]: nil=nil

We've created an empty table, and LuaJIT has allocated storage space for 0 array elements and 1 element in hashmap, whereto it has placed

nil key and nil value (i.e. nothing). Now let's try to populate this table:t["a"] = "A"

t["b"] = "B"

t["c"] = "C"

tostring(t)

-- table: 0x40eae3a8

-- a[0]:

-- h[4]: b=B, nil=nil, a=A, c=C

String keys are added to hashmap as expected. Here the first reason already becomes visible why the internal representation of tables may differ: hash collisions. To resolve hash collisions, LuaJIT uses a hybrid of open addressing and separate chaining methods [5] (thanks to Igor Munkin for clarification).

Depending on the order in which elements are added to the table, their order during integration will differ. For demonstration, I've set up one more auxiliary function

traverse(), which runs for cycle through the table and prints out its contents.Implementation of traverse

A complete version of the code can still be found on GitHub [4]. For brevity, I'm going to demonstrate here only its operating principle.

function traverse(fn, t)

local str = ''

for k, v, n in fn(t) do

str = str .. string.format('%s=%s ', k, v)

end

print(str)

end

t1 = {a = 1, b = 2, c = 3}

tostring(t1)

-- table: 0x40eaeb08

-- a[0]:

-- h[4]: b=2, nil=nil, a=1, c=3

t2 = {c = 3, b = 2, a = 1}

tostring(t2)

-- table: 0x40ea7e70

-- a[0]:

-- h[4]: b=2, nil=nil, c=3, a=1

traverse(pairs, t1)

-- b=2, a=1, c=3

traverse(pairs, t2)

-- b=2, c=3, a=1

One more interesting fact about the internals of tables: deletion of value does not lead to deletion of key. Sounds like Captain Obvious, but it's true.

t2["c"] = nil

traverse(pairs, t2)

-- b=2, a=1

tostring(t2)

-- table: 0x411c83c0

-- a[0]:

-- h[4]: b=2, nil=nil, c=nil, a=1

print(next(t2, "c"))

-- a

This is done for a purpose, to make it possible to delete values and not disturb iteration order. What is strongly discouraged is to add new keys to the table within the cycle as reallocation or re-hashing may occur, and then iteration will bust.

Additional note from Igor Munkin: the reason is lookup in general, not iteration. Collisions are resolved by the chain method. Generally, when the main node is deleted for the searched key, the link to the colliding element needs to be reassigned to the predecessor (if present) of this main node. Task O(n) to search for it needs to be performed when deleting. The cost of a search does not worsen when a dead node is present on the way to collision resolution. See also [5].

Arrays

OK, iteration for string keys is clear, no more questions. Now let's talk about the second half of the table — the array.

t = {1, 2}

tostring(t)

-- table: 0x41735918

-- a[3]: nil, 1, 2

-- h[1]: nil=nil

Lua is often made fun of because indexation in this language starts with one. Interestingly, LuaJIT allocates space to store the null element anyway. This makes it easier for it to avoid multiple addition / deduction of one.

If it appears to you that arrays don't have any surprises, then I'm here to disappoint you (or make you happy) — they do:

t = {[2] = 2, 1}

tostring(t)

-- table: 0x416a3998

-- a[2]: nil, 1

-- h[2]: nil=nil, 2=2

I've changed syntax a bit, so one element gets to the array, and another gets to the hashmap. So consider yourself warned: it's no use taking guesses about internal representation as your guess can turn out to be wrong at any time.

FAQ: WAT?

Answer: LuaJIT interpreter, same as regular Lua, generates different bytecode in these two cases.

In the first case, space is allocated to place two array elements, which is logical.

$ luac -l - <<< "t1 = {1, 2}"

1 [1] NEWTABLE 0 2 0 -- 2 to array, and 0 to hashmap

...

In the second case, 1 element in the array and 1 in the hashmap.

$ luac -l - <<< "t2 = {[2] = 2, 1}"

1 [1] NEWTABLE 0 1 1 -- 1 to array, and 1 to hashmap

...

But, still, my primary concern as a developer is the correctness of my code. If LuaJIT is comfortable with presenting tables differently, it has the right to do it this way. For me, the main thing is that it is done seamlessly. So I suggest that we go over functions and spell out the expectations.

Iterator pairs()

Iterator

pairs() has already been mentioned here earlier. It does not guarantee the iteration order. Even in an array. From the inside of LuaJIT, pairs() runs in sequence, first over the array, then over the hashmap. So if a numerical key gets to hashmap some way, then iteration order will be disturbed:t = table.new(4, 4)

for i = 1, 8 do t[i] = i end

tostring(t)

-- table: 0x412c6df0

-- a[5]: nil, 1, 2, 3, 4

-- h[4]: 7=7, 8=8, 5=5, 6=6

traverse(pairs, t)

-- 1=1, 2=2, 3=3, 4=4, 7=7, 8=8, 5=5, 6=6

FAQ: WAT?

Answer: Function

table.new(narr, nrec) pre-allocates the required storage space — this is the binding of standard function lua_createtable(L, a, h) from Lua C API. If table size is known beforehand (e.g., in the case of copying), this can be used to save on reallocations when the table is subsequently populated.This trick works exclusively due to pre-allocation. Another element being added to the table and the following re-hashing (which is a rather expensive and complex operation) will totally remove the veil of mystery from the table:

t[9] = 9

tostring(t)

-- table: 0x411e1e30

-- a[17]: nil, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, nil, nil, nil, nil, nil, nil, nil

-- h[1]: nil=nil

By no means do I want to sound paranoid, and I consider this case highly implausible. In 99.9% of instances, «arrays» in Lua will really be represented by arrays, and the iteration order will be sequential.

Table length table.getn()

Much more often, errors do occur because of array length being calculated incorrectly. The main thing one needs to know about it is a definition from Lua specification [6].

3.4.6 – The Length Operator

The length of a table t is only defined if the table is a sequence, that is, the set of its positive numeric keys is equal to {1..n} for some non-negative integer n. In that case, n is its length. Note that a table like

{10, 20, nil, 40}

is not a sequence, because it has the key 4 but does not have the key 3. (So,

there is no n such that the set {1..n} is equal to the set of positive numeric keys of that table.) Note, however, that non-numeric keys do not interfere with whether a table is a sequence.

That is to say, not every table has the property of length. Surprise — undefined behavior can occur in Lua. Tables with «holes» simply don't have such a property. In LuaJIT implementation, function

lj_tab_len [7] is commented as follows: /*

** Try to find a boundary in table `t'. A `boundary' is an integer index

** such that t[i] is non-nil and t[i+1] is nil (and 0 if t[1] is nil).

*/

MSize LJ_FASTCALL lj_tab_len(GCtab *t);

LuaJIT searches for a «boundary» in the table. If there are missing values in the array, and thus several boundaries exist, then, depending on the circumstances, LuaJIT will be able to find any of those — and will be right:

print(#{nil, 2})

-- 2

print(#{[2] = 2})

-- 0

FAQ: WAT?

Answer: These two tables differ in terms of internal representation.

tostring({nil, 2})

-- table: 0x410d5528

-- a[3]: nil, nil, 2

-- h[1]: nil=nil

tostring({[2] = 2})

-- table: 0x410d5810

-- a[0]:

-- h[2]: nil=nil, 2=2

LuaJIT searches for a boundary with a binary search, and it first checks the last element in the array. If it exists, search proceeds to the hashmap, otherwise it continues in the array.

And this definitely does not sound paranoid as there have been such errors in the past. Table length is implicitly used in other functions, so undefined behavior is something you don't want to play with. To be fair, it should be noted that in arrays without holes, the behavior is strictly determined and does not depend on internal representation.

Table.sort() sorting

Table sorting always works within the range from 1 to

#t, and there is no way to influence this. So it is helpful to check input values in those functions which deal with a table as an array:local function is_array(t)

if type(t) ~= 'table' then

return false

end

local i = 0

for _, _ in pairs(t) do

i = i + 1

if type(t[i]) == 'nil' then

return false

end

end

return true

end

Lua allows length to exist though, even when string keys are present, but as far as we are talking about typical contracts of functions, hybrid tables rarely work.

Pack/unpack

Where do those arrays with holes really come from? A rare weird case, as it might seem. But nope, there are dangers lurking every step of the way:

local function vararg(...)

local args = {...}

-- #args == undefined behavior

end

Multiple periods here are not an ellipsis but rather a designation of a variable number of function arguments.

Then someone calls this function with arguments

vararg(nil, «err»), and here you are: your function handles a holed array. If one calls unpack(t) after this, then the tail may fall off (or it may not, depends on luck, because this is UB).Lua specification [8] reads:

6.5 – Table Manipulation

unpack (list [, i [, j]])

Returns the elements from the given table. This function is equivalent to

return list[i], list[i+1], ···, list[j]

except that the above code can be written only for a fixed number of elements.

By default, i is 1 and j is the length of the list, as defined by the length

operator #list.

To avoid inadvertent loss of tail, instead of implicit

unpack(t, 1, #t) always write expressly unpack(t, 1, n). But where to take this n from? The answer depends on what kind of table you've got. In the case of varargs, you can use table.pack() method, which returns a hybrid:t = table.pack(nil, 2)

tostring(t)

-- table: 0x41053540

-- a[3]: nil, nil, 2

-- h[2]: nil=nil, n=2

traverse(pairs, t)

-- 2=2, n=2

print(unpack(t, 1, t.n))

-- nil, 2 – It’s OK, it’s not UB

In LuaJIT (and in Tarantool),

table.pack function is inaccessible by default, but it can be enabled with flag of -DLUAJIT_ENABLE_LUA52COMPAT compiler. But it is even easier to implement this functionality manually:function table.pack(...)

return {..., n = select('#', ...)}

end

This is where black magic comes into play —

select('#', ...) [9] — but a detailed description of its mechanism simply would not fit into this article. I'd just give you a tip: this has to do with Lua stack [10] — the mechanism which provides an interface between Lua and C (Lua C API). Meanwhile, we've got to move on.Iterator ipairs()

This one is a good operator, predictable enough.

ipairs should be thought of as a shortened version of such while cycle as:local i = 1

while type(t[i]) ~= 'nil' do

-- do something

i = i + 1

end

No internal representation differences can affect it, and «holes» don't lead to undefined behavior — iteration simply stops.

t = {1, 2, nil, 4}

print(#t) -- UB

-- 4

traverse(ipairs, t) -- Not UB

-- 1=1, 2=2

Pitfalls of FFI

An attentive reader could have noticed that I have already used twice a strange expression

type(x) ~= 'nil'. Why not just x == nil? This is because LuaJIT, unlike PUC-Rio Lua, has a magic type cdata:ffi = require('ffi')

NULL = ffi.new('void*', nil)

print(type(NULL))

-- cdata

print(type(nil))

-- nil

print(NULL == nil)

-- true

if NULL then print('NULL is not nil') end

-- NULL is not nil

This is a notorious pitfall in Tarantool named

box.NULL. Note that condition if NULL is interpreted as true (unlike if nil), despite the fact that NULL == nil.Another pitfall in LuaJIT is the use of FFI types as a table key. This issue is not so frequently discussed in Lua manuals because there are no FFI types in vanilla version of Lua. But LuaJIT can surprise you and backfire. Here's what's written in the manual [11]:

Lua tables may be indexed by cdata objects, but this doesn't provide any useful

semantics — cdata objects are unsuitable as table keys!

A cdata object is treated like any other garbage-collected object and is hashed

and compared by its address for table indexing. Since there's no interning for

cdata value types, the same value may be boxed in different cdata objects with

different addresses. Thus t[1LL+1LL] and t[2LL] usually do not point to the

same hash slot, and they certainly do not point to the same hash slot as t[2].

Simply put, for

cdata-keys, hash is counted from the pointer (i.e. void*), so they show unpredictable behavior and should be avoided in practice at all cost. A joke from Tarantool life:tarantool> t = {1}; t[1ULL] = 2; t[1ULL] = 3;

---

...

tarantool> t

---

- 1: 1

1: 3

1: 2

...

tarantool> t[1ULL]

---

- null

...

I hope no one in one's right mind would write things like this in code, but

cdata is not infrequent, and this has occurred in the past. As an example, consider uuid [12] and clock.time64() from Tarantool. Or big values stored in spaces in unsigned format.As long as we are on this subject, note that it's possible to obtain unexpected results without using too, though I've never seen this in practice:

tarantool> t = {'normal one'}

t[1.0 + 2^-52] = '1.0 + 2^-52'

t[0.1 + 0.3*3] = '0.1 + 0.3*3'

---

...

tarantool> t

---

- 1: normal one

1: 1.0 + 2^-52

1: 0.1 + 0.3*3

...

Summary

- Table length operator

#tis only defined for arrays without holes. All the rest is Undefined behavior. - Function

ipairs()is iterated aswhile type(t[i]) ~= 'nil'— not for all keys, but, on the plus side, in a predictable way, and the order is guaranteed. - Function

pairs()is iterated for all keys, but the iteration order is affected by the internal representation of table. - Functions

unpack,table.sort,table.insert, andtable.remove, once called with default arguments, hold undefined behavior in them due to#t. - The use of «strange» (ffi) values in keys affords you plenty of ways to shoot yourself in the foot. They should be avoided.

References

[1] The basics and design of Lua table (or the same at slideshare.net).

[2] Programming in Lua — Tables

[3] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT — lj_obj.h

[4] GitHub — rosik/luajit:habr-luajit-tables

[5] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT — Issue #494.

[6] Lua 5.2 Reference manual — The Length Operator

[7] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT lj_tab.c

[8] Lua 5.1 Reference manual — Basic Functions — unpack

[9] Lua 5.1 Reference manual — Basic Functions — select

[10] Lua 5.1 Reference manual — The Stack

[11] GitHub — LuaJIT/LuaJIT — ext_ffi_semantics.html

[12] Tarantool » 2.2 » Reference » Built-in modules reference » Module uuid

[Bonus] Learn X in Y Minutes, where X=Lua